Making

an M1907-Style Rifle Sling

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

Now that I’ve restored a

Springfield

1903-A3 drill rifle to shooting condition (refer to my article

Reactivating

a Springfield 1903-A3 Drill Rifle) I wanted to put a

military-style sling on it.

This would be both for looks and for function.

During WWI and most of WWII the official sling used by

the

U.S.

military was the M1907 sling.

This is the sling that looks like someone dropped a

bowl of noodles onto the rifle because it has multiple

overlapping layers of leather.

This sling can be used to both carry the rifle and

provide support in different shooting positions.

Research on

the Internet brought up plenty of information about the

installation, use, and care of the M1907 sling, as well as

numerous suppliers of original or “authentic” replicas.

Just about every shooting supplier on the Internet

offered a replica sling, and there were many original WWI or

WWII slings for sale, especially from online auction sites.

I decided to purchase a replica at what I thought was a

reasonable price, but was very disappointed when the sling

arrived. It was

much wider than 1 1/4” inches so it would barely fit in the

sling swivels, and it was covered with some type of colored

hard finish which would not take any oil.

Rather than send it back I decided to use the hardware

from it and make my own sling.

I drilled out the copper rivets to remove the frogs,

and cut the stitching on the short strap so I could remove the

ring.

I’ve been

crafting leather now for over 33 years as an extension of my

shooting hobby. In

the late 1970’s – maybe 1979 – I read an article in Guns

and Ammo magazine where the author showed how to make a

custom leather holster. That

year my wife bought me a leather crafting set from Tandy

Leather and I’ve been making leather gear ever since.

Tandy Leather was absorbed by The Leather Factory and

became Tandy

Leather Factory (TLF).

They still produce leather crafting kits; a good basic

one is #55509-00.

This skill has

come in handy especially since it’s so difficult to find

holsters that fit handguns that have additional accessories

attached like lasers. Refer

to my article Making

a Custom Leather Holster for a Taurus® 24/7.

The M1907

sling is made up of seven parts:

- 1

short strap

- 1

long strap

- 2

keepers

- 2

claw hooks called frogs

- 1

ring

I found a

general description of the sling on the Internet which gave me

some broad specifications.

http://pronematch.com/a-short-history-of-the-the-sling/

“The

short strap is about two feet long, an inch and a quarter

wide, and quarter inch thick. [This

is way too thick!] A claw hook [frog]

fastened with three strong rivets is at one end and a metal

‘D’ ring is sewn on by means of a loop on the other end. Between

these two pieces of hardware are 16 pairs of punched holes. This

is the end of the [sling]

that attaches to the lower sling swivel of the rifle. Until

1938 the metal parts were made of blackened brass. This

was replaced by Parkerized steel, although some parts

manufactured during World War II were blackened steel.

The

long strap is about 46 inches long with a claw hook, also

called a ‘frog’, on one end and the opposite end, the feed

end, rounded off. The

sling weighs in at about a half of a pound. Ten

pairs of holes start from the feed end and progress toward the

center with another 18 pairs originating at the claw end. This

leaves about 16 inches of unpunched leather in between. The

long strap also includes two three quarter inch wide leather

loops known as sling keepers which are used to keep loose ends

tidy and the sling snug around the shooter’s arm. It

is [attached to] the

forward sling swivel.”

One other

reference indicated that the short strap measured 1 1/4” x

24”, and the long strap measured 1 1/4” x 48” inches.

The short strap requires an extra 2.5 inches to make

the loop to hold the ring, so all together I needed about

75-inches of 1 1/4” leather.

Through trial and error I discovered that the short

strap needed to be 22” for the

Springfield

1903-A3, and 24” for the M1 Garand.

Because I couldn’t find original drawings or complete

specifications for the sling I purchased a WWI “relic” from

ebay for $7.00 including shipping. The keepers were missing

and the short strap was torn in two places; however the

metal hardware was intact which I can remove. I used this

1918-dated relic to get the measurements I needed.

Choosing

the Leather

Leather is sold by thickness but it is measured in ounces.

One ounce is 1/64 of an inch.

8-9 ounce leather makes the best rifle slings; 8/64 =

1/8 which is half the thickness of 1/4 as stated above.

TLF sells natural cowhide leather strips in different

widths and lengths, all are made of 8-9 ounce leather.

Their longest strips measured 72 inches which was

perfect for what I needed.

I purchased one 72-inch strip 1 1/4” wide #4530-00

which gave me enough leather to make the sling.

It is my understanding that the original military

slings were made of raw leather and frequently oiled to give

them that deep, rich brown color, so I decided to make mine

out of natural leather and would apply my own oil and finish.

Another

good choice for sling leather would be latigo leather which

has already been oiled. TLF

sells these in 72” lengths #4764-00

and they are also made of 8-9 ounce leather.

Latigo leather can leave oil stains on clothing so it

needs to be sealed with some type of finish to prevent the oil

from leeching out onto clothing.

Making

the Straps

I cut a

48” strap from the 72” blank and rounded one end leaving

one end squared. I

will attach the frog to the square end.

That left a 24” strap with square ends that I left

alone. I will

attach the second frog to one end, and the other end will be

split and folded over to make a loop for the metal ring.

Punching

the holes

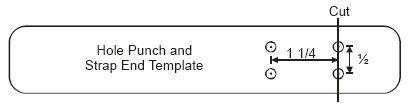

In

order to get the holes properly and evenly spaced I created

a template from heavy card stock. After measuring the relic

sling I spaced holes 1/2” apart, with

1 1/4” between each pair of holes. The template also

provided the pattern so I could round off one end of the

long strap.

I

started marking holes 3” inches from the frog end of the

short strap; refer to the specification drawings above. I

used the template to mark the locations of the holes using

the pointed end of a modeling tool

#8039-06. I moved the template so the holes at the end

were centered over the two marks I made previously, then

marked the next set of holes. I used a 3/16” x 9/32” oval

hole punch from the oval punch set

#3005-00 to punch 16 sets of holes. On the long strap,

I punched 16 pairs of holes 1 1/4” apart starting 2 3/8”

from the frog end, and 10 pairs of holes 3/4” from the round

end.

I took my

grooving tool #8069-00

and adjusted it to 1/8” and cut a stitching groove

completely around each strap.

This gave it an authentic, professional look.

To give the

strap a rounded edge I first took my #3 edge beveler #8076-03

and beveled both the front and back edges of both straps.

This removed the sharp, square edge of the leather.

Then I took a small wet sponge and moistened the

beveled edge, then rounded the edge with an edge slicker #8122-00.

This process also gave the leather a finished,

professional look.

The last 1

1/2 inches of the loop end of the short strap I split to 1/2

the thickness so I could fold over the leather.

I split the flesh (rough) side of the leather, not the

smooth (hair) side. I

used my Heritage leather splitter which apparently TLF no

longer sells. Their

Craftool version

is a fairly expensive tool, but you can do the same with a

skiving tool #3025-00

or a single-edge razor blade.

Finishing

the Leather

There are many types of leather finishes available including

dyes, waxes, creams and lotions, and even varnish or lacquer.

Based on my research, original M1907 slings were made

of unfinished leather, but treated with neatsfoot oil to make

them supple and to provide some protection against drying out.

Later slings were treated with a mildew-resistant

chemical, but I don’t plan to have my sling out in the rain.

Neatsfoot

oil will discolor the leather, which is exactly what I wanted.

One resource on the Internet showed how one coat of

neatsfoot oil turned the leather to a rich brown color, but it

seemed for my leather one coat was not enough.

Even after three coats of neatsfoot oil, once the oil

dried the leather returned to its pale, but somewhat darker,

original color indicating it would take many coats of oil to

get to the proper shade.

In order to

get the color I desired I poured some neatsfoot oil into a

plastic bowl and submersed the leather into the oil.

I didn’t let it soak, just left it there long enough

for the leather to change to the color I desired.

I removed the strap and wiped the excess oil off with a

paper towel, then hung the strap up to dry.

Once the

oil dried I applied a coat of Fiebing’s Aussie Leather

Conditioner #2199-00

which contains beeswax. This

sealed the leather to prevent any oil from leaching out of the

leather and made it somewhat waterproof.

It also made the sling slide through the sling swivels

and keepers easier because of the wax finish.

Attaching

the Hardware

Although I used the hardware from an existing sling,

Brownells sells the frogs

#084-270-006WB. Ryan Loeppky, a reader of The Kitchen

Table Gunsmith found an unusual source for the sling rings.

Ryan discovered that Home Depot sells a steel chain that the

individual links are the correct size for the ring. The

model number is

806446 #2/0 Steel Straight Link Chain store SKU#

263436. I found it in the aisle that sells bulk chain for

$1.15/foot. Their web site states this must be purchased in

the store, which makes sense since they are going to cut it

off of the bulk reel.

Photo

courtesy Ryan Loeppky

Ryan cut

the two adjoining links to separate one link. He polished

the weld so it wouldn't cut into the leather, then sanded

off the zinc plating. Finally he cold-blued the link so it

would match the frogs he purchased from Brownells as

described above. Because the link is welded this makes a

very strong sling ring. Thanks Ryan for sharing this great

idea.

Once

the leather was finished I attached the hardware I removed

from the poor quality sling.

I laid the frog on the square end of each strap, marked

the locations of the three rivet holes, then used my rotary

hole punch #3240-00

to punch the holes for the rivets.

The frogs

were attached to original M1907 slings with copper rivets.

I used small, black double-cap rivets #1371-13

to attach the hardware. I

used black to match the color of the hardware.

I inserted the stem of the base through the frog and

into the leather. I

set the cap onto the stem through the back of the strap using

my rivet setter #8105-00.

I set the cap deeply into the back of the leather strap

so it was flush with the leather.

In this way it wouldn’t drag against the other strap.

I folded

the split end of the short strap, installed the ring, punched

two holes, then installed two of the black double-cap rivets.

The loop was sewn on original M1907 slings but I

decided to use rivets because they’re easier to install.

Keepers

The M1907 sling has two keepers to help keep the straps in

place. I cut two

strips of 8-9 ounce leather 3/4” wide by 2 1/2” long.

I grooved, beveled, and slicked each strip as

previously described. I

split both ends to 1/2 the thickness; the end that would lay

on top I split the flesh side, the end that would lay on the

bottom I split the hair side.

I split the ends because I didn’t want the keeper to

be so thick where I riveted the ends together. I soaked each

strap in water for about 30-seconds, then wrapped it around

two thicknesses of sling strap.

This wet-molded the keepers to the proper shape so they

fit perfectly and would be nice and tight.

Once the

leather dried I dunked each strap into neatsfoot oil, wiped

off the excess, allowed it to dry, then applied the leather

conditioner.

I wrapped

each keeper around two thicknesses of sling strap as I did

before and marked the outside end where I wanted to punch the

two rivet holes. After

I punched the holes, I again wrapped the keeper around two

thicknesses of sling strap and marked the inside end and

punched the rivet holes. Once

the holes were punched I attached two of the black double-cap

rivets to hold the keeper together.

Attaching

the Sling

Ok, so now that I have this “spaghetti” of leather, how do

I attach it to my rifle? It’s

really not so difficult once you do it a couple of times:

Step 1:

Run the hook of the short strap through the rear sling

swivel so the ring is against the rifle and the hooks of the

frog are facing the rifle.

Step 2:

Put one keeper onto the long strap so the rivets are on

the back (non-stitching groove) side of the strap.

Step 3:

Feed the round end of the long strap through the ring

of the short strap so the front (stitching groove) side of the

long strap is against the rifle and the hooks are facing the

rifle. Note the orientation of the long strap in the

above photo.

Step 4:

Feed the round end of the long strap through the keeper

you installed in step 2 above.

Step 5:

Attach the hooks of the short strap into the first set

of holes below the frog of the long strap.

Step 6:

Put the second keeper onto the long strap so the rivets

are on the front (stitching groove) side of the strap and

against the rifle.

Step 7:

Feed the round end of the long strap through the front

sling swivel, then back through the second keeper you

installed in step 5 above.

Step 8:

Attach the hooks of the long strap to any hole in the

rounded end of the long strap.

I found the third set of holes from the rounded end

worked best for me by loosening the strap and inserting the

frog into the set of holes so the strap was loose enough to

sling the rifle over my shoulder.

Adjusting

the Sling

The sling can easily be loosened or tightened (dressed) by

pulling on the inside and outside sections of the long strap

in opposite directions.

Referring

to the above photo, pull the outside of the long strap towards

the muzzle, and pull the inside of the long strap towards the

butt to tighten the sling.

Pull the outside of the long strap towards the butt,

and pull the inside of the long strap towards the muzzle to

loosen the sling. (The

beeswax conditioner I applied to the leather makes this fairly

easy to accomplish.)

Using

the Sling for Shooting Support

The purpose of the sling is to not only allow you to

conveniently carry the rifle, but to also provide additional

support in the prone, sitting, and kneeling positions.

Step 1:

Loosen the sling, then remove the lower frog and attach

it to the second or third pair of holes on the frog end of the

short strap. This

keeps the strap anchored and prevents it from flopping around.

Step 2:

Move the upper frog to an appropriate pair of holes in

the rounded end of the long strap.

For me I found I didn’t have to move this frog at

all. You will have

to experiment to find what pair of holes and sling adjustment

works best for you.

Step 3:

Move the lower keeper up the strap to expose a loop of

leather.

Step 4:

Rotate the sling 1/2 turn to the left for a

right-handed shooter.

Step 5:

Place your left arm through the loop and pull the loop

up above your bicep. Tighten

the keeper so the leather loop stays in place.

Tighten the upper keeper close to the upper sling

swivel.

Step 6:

Place the back of your left hand against the sling and

grip the stock close to the upper sling swivel.

The sling should be fairly tight, but not

uncomfortable.

Step 7:

Once you have attained the prone, sitting, or kneeling

position move the butt of the rifle to your shoulder.

You should have to push the butt forward against the

tension of the sling to get the butt to fit snuggly against

your shoulder. The

sling should be tight in order to provide proper support.

If I had a shooting jacket and glove there would be no

space between the back of my hand and the sling in the above

photo.

|