Pressure Testing Homemade .45 Colt Shotshells

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

I was surfing the Internet one day and found a YouTube video

by MannyCA on how to make .45 Colt shotshells using tools

and materials I already had on hand; the link to the video

is below.

Making .45 Colt Shotshells by MannyCA

WARNING: These loads are

over-pressure loads and should only be used in Ruger or

Contender handguns!

He also

has a video on shooting these homemade shotshells showing

their effectiveness. Handgun caliber shotshells can be very

effective against rats, snakes and other small varmints if

you get close enough. Often times you are right on top of a

snake before ever seeing it, which makes it close enough for

these shotshells to be effective. That’s why they are

sometimes called snake shot. When I hike through the woods

I carry a .45 Colt Ruger Blackhawk revolver and usually my

first two rounds are shotshell loads.

Assembling the Loads

Following MannyCA’s video I made my own .45 Colt shotshell

loads using the following materials:

-

Stiff

Cardboard – Any source of stiff cardboard will work; I

used a 12-gauge shotshell box, but cereal boxes and

canned beverage boxes work great as well.

-

Wad

Cutter – This is made from a resized and sharpened .45

Colt shell casing. I resized a case, then sharpened the

mouth with my chamfering tool and wrapped some blue

painter’s tape around it so I wouldn’t mistake it for a

reloadable case. I was surprised just how tightly my

cardboard wads fit in the case!

-

Standard .45 Colt Reloading Dies

-

Reloading Press

-

Powder – For my test loads I used Unique, Red Dot and

Green Dot.

-

#8

shot – 160 grains

-

Dippers

-

Powder funnel

-

Scale

– beam or digital to weigh powder and shot

-

Gas

Checks (optional) – The gas check is used to cap the

shot, but you can use a cardboard wad as well.

I had all

these materials at home already so I didn’t have to go out

and buy anything. MannyCA used 9.5 grains of Unique, but I

wondered why he used this amount and if this load generated

excessive pressure. He was shooting them out of a Ruger

Blackhawk, the new mid-size model, so even if the pressure

was beyond the SAAMI maximum, it might not be a problem for

the Blackhawk. The online

Alliant Powder reloading manual gives 8.5 grains of

Unique for a 230 grain cast lead bullet as maximum at 850

feet per second, but did not provide any pressure data.

Since the shotshell uses only 160 grains of shot, 9.5 grains

of Unique might be alright; but how would I know without any

data? And what about other powders; would there be pressure

issues using other powders? I had 8-pound kegs of both Red

Dot and Green Dot so I decided to test some shotshell loads

using these other powders. My theory was that there would

be a pressure spike to get the shot column moving out of the

case, but would drop off quickly once the shot spread out.

I also thought that the pressure spike would be lower for

shot than for a solid bullet because gas would escape around

the shot once it left the case. (Wow was I wrong on that

theory; read on!) The only way to know was to perform

pressure testing.

Powder

Volume

I started with MannyCA’s recipe of 9.5 grains of Unique. I

discovered that Lee powder dipper 1.3cc threw about that

amount of powder. I wanted to keep the volume of powder the

same because I wanted it to take up the same amount of space

in the case, or less. Different powders have a different

load density; in other words, the same weight of different

powders will take up a different amount of space (have a

different volume). Looking at it the other way; the same

volume of different powders will have different weights.

I used

the 1.3cc Lee dipper because that left me enough space in

the case to load 160 grains of #8 shot and cap it with a .45

gas check. Using the 1.3cc Lee dipper gave me the following

powder weights:

|

Powder |

Weight (grs) |

|

Unique |

10.0 |

|

Red Dot |

8.5 |

|

Green Dot |

9.5 |

I

backed-off the Unique weight to 9.5 grains to match

MannyCA’s load and used a powder scale to accurately measure

the powder. These were the starting weights of powder with

which I performed my pressure measurements.

Although

I used the same size dipper for each load, I discovered that

9.5 grains of Green Dot filled the case too much so I had

trouble seating the gas-check on top. If I was to use this

load I would probably back this off to 8.5 grains. As you

can see in the above photo, each load is labeled; U for

Unique, R for Red Dot, and G for Green Dot.

Installing a Strain Gauge

I found a

used

Thompson/Center Contender® with a .45 Colt/410 barrel on

Gunbroker for a very reasonable price. Not only will

the Contender allow me to attach a strain gauge over the

chamber, I can purchase additional barrels to test other

calibers, not to mention it’s a fun gun to shoot.

When I

performed the pressure measurements for my .45 Colt hog

loads I attached a strain gauge to the barrel of my

Marlin 1894 Cowboy rifle. Because the .45 Colt case is

so short most of the chamber was under the receiver threads

so I could only measure pressure at the mouth of the case,

not over the center of the case as recommended.

I

fabricated a strain gauge assembly by attaching 30-gauge

wires and a connecter to a strain gauge. Rather than using

the 28-gauge stranded wire which had a tendency to break

(refer to my article

Strain Gauges for Chamber Pressure Measurements) I

used 30-gauge solid wire-wrap wire available from

Radio Shack. I placed a dab of Armstrong A-12 epoxy on

the soldered ends of the strain gauge and on the back of the

connector to act as strain relief so the wires wouldn’t

break during handling.

I removed

the rear sight blade assembly and attached the gauge to the

Contender barrel over the chamber using JB Weld epoxy. I

couldn’t get it over the center of the chamber because of

the rear sight base. Even though I had covered the soldered

connections on the strain gauge with A-12 epoxy, I was

careful not to get any JB Weld on those connections because

JB Weld has iron in it so it is not electrically insulated.

The A-12 epoxy didn’t seem to harden; it stayed tacky which

is why I decided to use the JB Weld. The blob of epoxy on

the side of the barrel in the above photo acts as strain

relief so I’m not moving the wires on the strain gauge

connections.

Measuring

Pressure

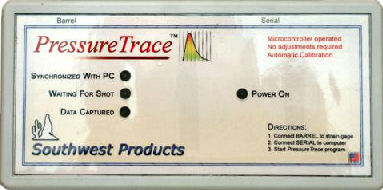

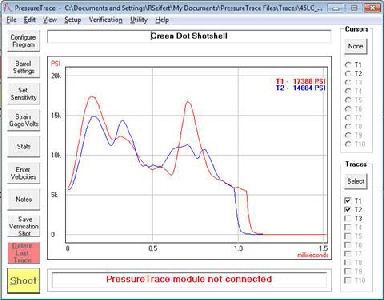

The

strain gauge is connected to the excellent

PressureTrace™ device available from

Recreational Software, Inc., which in turn is connected

to my laptop via the serial RS232 port. I have the older

RS232 version; the newer version connects to a computer via

a wireless Bluetooth connection. The Pressure Trace device

measures and amplifies the slight voltage change in the

strain gauge caused by the barrel expanding when a round is

fired. The software running in the laptop converts that

reading into pressure in PSI and graphs it on the display.

The SAAMI

maximum pressure for .45 Colt is 14,000 PSI so I wanted my

shotshell loads to be at or below this figure. That would

make them safe in both the heavier Rugers and Contenders,

and lighter Colts and Colt clones.

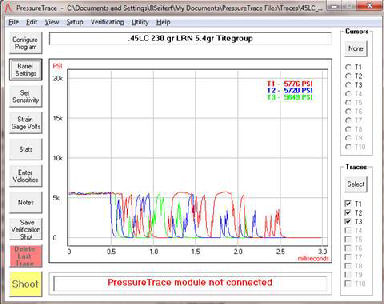

I first

calibrated the Pressure Trace device by firing a

verification load of 5.4-grains of Titegroup powder under a

230-grain cast lead round nose bullet. This is my normal

cowboy load that chronographs at 740 feet per second. All

of my reloading manuals show .45 Colt loads in copper units

of pressure (CUP) so I made an assumption. Since the SAAMI

maximum pressure for .45 Colt is 14,000 PSI my cowboy load

should be below that since it is far from the maximum load

of 6.5-grains of Titegroup. I did a rough ratio and

proportion calculation and assumed that if 6.5-grains of

Titegroup equaled 14,000 PSI (just a guess on my part since

no pressure data was available), then 5.4-grains would equal

in the neighborhood of 11,600 PSI.

My cowboy

loads averaged 5,719 PSI. This makes sense since test

barrels have a very tight chamber which generates higher

pressure readings. My Contender has a commercial chamber so

the readings would be lower. Once the device was calibrated

I began testing my shotshell loads.

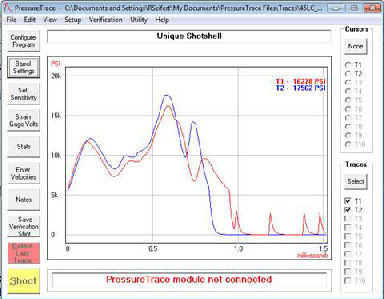

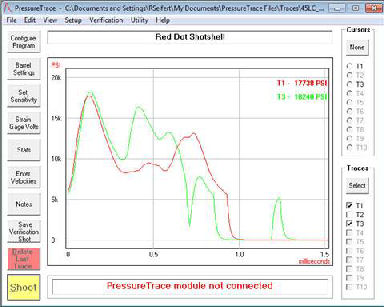

I fired

three loads of each different powder to get an average

pressure reading. I eliminated the highest of the three

readings; the results are in the following table.

|

Powder |

Weight (grs) |

Pressure (PSI) |

|

Unique |

9.5 |

16,920 |

|

Red Dot |

8.5 |

17,989 |

|

Green Dot |

9.5 |

16,136 |

To my

surprise all three loads were over the SAAMI maximum

pressure of 14,000 PSI! This is probably safe in Ruger

single-actions and Contenders, but not for an original Colt

that was designed to shoot only black powder, low-pressure

loads. I would even question using these loads in modern

Colt clones! I would probably reduce each load by at least

1.0 full grain to get them within the SAAMI maximum pressure

specification.

Summary

I have a personal philosophy to never shoot someone else’s

reloads, nor use someone else’s handload recipe. I have had

problems in the past with other people’s reloads; I damaged

my son’s M1 Garand barrel because we were shooting gun show

reloads (refer to my article

Rebarreling Two M1 Garands). Reloading manuals

contain safe handload formulas that have been thoroughly

tested and should be followed; not someone’s personal pet

load. Pet loads should be verified against published

reloading data. Someone’s personal recipe may just be a

recipe for disaster!

|