Fitting a

.45 ACP Conversion Cylinder

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

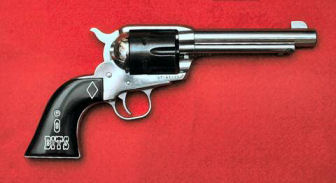

A little while ago my friend Chili Ron showed me a

stainless-steel large-frame Ruger Vaquero that came with two

cylinders; one in .45 LC (Long Colt), and a second one in

.45 ACP (Automatic Colt Pistol). I thought that was a great

idea, and I’m a big fan of convertible revolvers. I own two

Ruger Single Six convertible revolvers that came with two

cylinders; one for .22 short/long/long rifle, and a second

one for .22 magnum. I converted one of those Single Six

revolvers into a trail gun, refer to my article

Building the Ultimate .22 Trail Gun. I thought it

would be fun to shoot .45 ACP out of my Ruger large-frame

.45 LC Vaqueros, not to mention the lighter rounds would be

good for cowboy action shooting. .45 ACP is the caliber

also used for Wild Bunch matches in 1911 pistols.

I found a

Ruger .45 ACP cylinder on eBay that came from an old-model

Blackhawk for a fairly reasonable price. Ruger used to

provide their extra cylinders in a red felt bag; the spare

cylinder for my Single-Six liberty gun had one. The problem

with these bags was that they absorbed moisture. Most

people never removed the spare cylinder from the bag so

eventually the cylinder developed rust as you can see from

the above photo.

This

cylinder had been fired, but never cleaned; I hate working

on dirty guns. If I were a professional gunsmith I would

charge an extra $40 just for cleaning! I soaked a cleaning

patch in

Ed’s Red and liberally swabbed each chamber. I then put

a .45 caliber bronze cleaning brush on the end of an

aluminum rifle cleaning rod segment and chucked the rod into

my cordless drill. I ran the drill at a slow RPM and moved

the brush in and out of each chamber. Years of dried, caked

on power residue came off in my hand. I dried each chamber

and coated each one with Breakfree CLP.

Fitting

to the Frame

I tried

fitting the cylinder into my .45 LC Bisley Blackhawk but it

just wouldn’t fit. After some careful examination I

discovered that the .45 ACP cylinder was longer than the

Blackhawk cylinder. This was because the rims of .45 LC

cases sat above the rear face of the Blackhawk cylinder, but

.45 ACP cases sit flush and even with the rear of the .45

ACP cylinder. The cylinder had to be longer so the firing

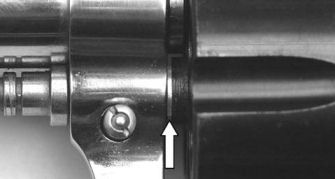

pin could reach the primers. The rear outside edge of the

.45 ACP cylinder was hitting a raised ridge left in the rear

bottom corner of the frame as shown in the above photo.

This ridge was obviously left over from the manufacturing

process.

Both of

my Vaqueros had this same ridge. I carefully filed off the

ridge with a safe-edge file until the corner was square and

the edges were flat. Now the cylinder fit into the frame

and rotated freely.

Milling

the Ratchet

The diameter of the ratchet for the .45 ACP cylinder

measured 0.611”, but the diameter of the ratchet for my

Vaqueros and new model Blackhawks measured 0.560”. Although

the cylinder functioned properly, and was timed properly, my

homemade free spin pawls no longer worked. (Refer to my

article

Making a Free Spin Pawl for a Ruger® Single-Action Revolver.)

The ratchet was so wide it was still engaging the top tooth

of the pawl.

The front

pivot on the cylinder measured 0.435” wide by 0.095” high,

so I milled a 0.436” hole 0.100” deep in a piece of aluminum

I had set up and leveled for another project. I set the

cylinder in the hole with the ratchet facing up and secured

the cylinder in place. I carefully centered the mill and

milled the outside of the ratchet. I milled down 0.100”

because I didn’t want to touch the face of the cylinder.

This left a small raised ring of metal around the ratchet,

but this does not interfere with the cylinder. After the

milling was completed I cold-blued the exposed metal. The

cylinder now functioned perfectly just like my other

cylinders.

End Shake

Although

the cylinder now fit into the frame, there was a large gap

between the frame and the end of the cylinder. This is

called “end shake” and when it is pronounced like this will

cause the front of the cylinder to rub against the rear of

the barrel and possible misfires caused by the cylinder

moving away from the firing pin.

This gap

measured 0.030” so I fabricated an end shake shim to keep

the cylinder in position. I took a piece of 3/64” tool

steel and milled it down to 0.030”, then milled out the shim

with my hobby CNC mill. The center hole measured 0.270” and

the outside diameter was 0.436”. I polished the side of the

shim that rotated against the frame with 1,000-grit paper to

make it very smooth.

The end

shake shim fit perfectly; it allowed the cylinder to rotate

freely with just a hint of front-to-back movement. To

hold the new shim in place I used a toothpick to spread a

thin layer of superglue gel on the surface of the shim and

set it in place onto the front of the cylinder. I prefer

using the gel because it doesn’t run all over the place like

the liquid does. I

ran a piece of 1/4-20 threaded rod through the pivot hole

and snugged a 1/4“ washer and nut on each end. I left the

nuts and washers in place for 24 hours to allow the adhesive

to set up. Now I can install and remove the cylinder in the

frame without having to worry about losing the end shake

shim.

Summary

So now I have one Vaquero with an interchangeable .45 ACP

cylinder. The cylinder did require some minor fitting. I

really didn’t have to reduce the circumference of the

ratchet, it would have worked perfectly well in an

unmodified Vaquero, but it wouldn’t work with my homemade

free-spin pawls. I also didn’t have to fabricate the end

shake shim; Brownells sells a 10-pack of 0.0045” Single

Action Revolver Gas Ring Shims

#713-000-080 which I could have stacked to fit.

Now all I have to do is polish out and remove all the

pitting left from the rust and refinish the cylinder. This

will be another article.

Addendum

It wasn’t any more than a week after I published this

article that another Blackhawk .45 ACP cylinder appeared on

ebay. My friend Chili Ron was right; they do show up

regularly! This one fit in my second Vaquero almost

perfectly, and the blued finish was flawless with no rust.

Because it had been fired it had the drag ring around the

outside, but unlike the first cylinder this one had been

cleaned.

The

ratchet measured 0.577” and was just barely touching the top

tooth of my homemade free-spin pawl. I reduced the diameter

of the ratchet to 0.560” and cold blued it to match my other

cylinders.

This

second cylinder was shorter than the first one; the rims of

the .45 ACP cartridges sat above the rear face of the

cylinder rather than flush like the first cylinder I

purchased. Both cylinders in the above photo have a

cartridge in one of the chambers, but the rim of the

cartridge is exposed in the right cylinder.

I drilled

and tapped a 1/4-20 hole in the center of the 0.436” hole I

milled in my jig. I mounted the first cylinder in that hole

with the ratchet up and secured it with a 1/4-20 rod and a

nut.

I milled

0.038” off the rear face of the first cylinder so the rims

of the cartridges would sit above the cylinder face like the

second cylinder. This left a lot of bare metal exposed but

I plan to refinish this cylinder anyway. I beveled the rear

edge of the cylinder, and chamfered the chambers to remove

the sharp edges left from the milling process. The raised

rims make it easier for the loading marshal to see an empty

chamber during a cowboy match. It is almost impossible to

see an empty chamber if the cartridge rim sits flush with

the rear face of the cylinder.

There was

a 0.014” end shake gap so I had to fabricate an end shake

shim like I did before. The shim I fabricated was just a

bit too thick so I polished it with 400-grit wet/dry sand

paper until the cylinder rotated freely. I again used

superglue gel to hold the shim in place.

I took an

electric engraver and engraved the last three digits of the

Vaquero’s serial number on the front face of each cylinder

similar to the way Ruger does at the factory so I can tell

which cylinder goes with which gun. Now both of my Vaqueros

have a .45 ACP conversion cylinder.

Addendum

02/19/2020

I have had some readers of The Kitchen Table Gunsmith tell

me that super glue is probably not the best method for

attaching an end shake washer to the cylinder. As it turns

out, they were right. The blast coming from the barrel to

cylinder gap caused the super glue to loosen, and when I

took the cylinder out for cleaning, I would have to chase

after that little washer. Loctite didn’t hold the washer

either.

There are

three schools of thought on how to fix end shake:

1.

Install

end shake washers like I did in the first place. This works

well for a double-action revolver because the washer is

captured, but not so well for a single-action revolver.

2.

Stretch

the gas ring. The gas ring is the front part of the

cylinder that sets against the frame. This can be stretched

to take up the cylinder to frame gap. This worked for one

of the cylinders, but not both.

3.

Install a

base pin bushing like a Colt Single Action Army. Now that I

have a lathe, I could mill out the center of the cylinder to

7/16” – the width of the gas ring – and fabricate a

stainless-steel bushing with an outside diameter of 7/16”

and an inside diameter of 1/4”. I did this for the other

cylinder.

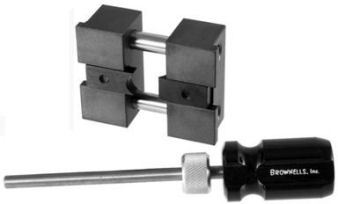

Brownells sells a

Single Action Gas Ring Stretcher designed to work with

Ruger single-action revolvers. The instructions say to

stretch the gas ring 0.015” to 0.025” longer than required,

then polish the front of the gas ring with 320-grit paper

and the support tool to achieve the appropriate fit. My

wife bought me the gas ring stretcher for Christmas, so I

decided to use that method.

I turned

two brass pins that fit into a chamber. I discovered that

the stretching tool clamped the gas ring so tightly I

couldn’t turn the cylinder. The two brass pins allowed me

to use a metal bar to turn the cylinder.

I placed

the stretching tool in my vise with bronze jaws so I

wouldn’t damage the tool. I put painter’s tape on top of

the tool so I wouldn’t scratch the cylinder. I placed a

Ruger cylinder base pin through the base pin hole from the

bottom so it wouldn’t interfere with the bar. The base pin

prevented the hole from collapsing. The instructions said

to use the support pin in the base pin hole, but then I

couldn’t turn the cylinder with a tool. I lubricated the

gas ring, then set the cylinder so the ratchet was up, and

the gas ring was down in the tool.

I

tightened the vise until the stretching tool was tight

against the gas ring. I used an AR-15 tool between the pins

to turn the cylinder while pressing down to keep the

cylinder even. I tightened the vise and turned the cylinder

until the gas ring measured ~0.015” over my target length.

I used

220 and 320-grit polishing sticks to reduce the length of

the stretched gas ring, then final polished with a piece of

400-grit wet/dry sandpaper against the flat end of a

cylinder base pin. I polished and tried for fit frequently

until the cylinder fit into the frame. The diameter of the

base pin hole was reduced a bit at the gas ring, but I ran a

1/4” square end milling bit to open it up, then chamfered

the hole with a countersink bit. Now this cylinder fits

perfectly in my Vaquero and I don’t have to worry about

losing that pesky little end shake washer!

After

stretching and polishing, the gas ring looks like the above

photo. There is not as much bearing surface as factory, but

it should suffice. The stretching process left a sharp

outer edge on the gas ring, but the polishing made that edge

flat. That’s why the instructions say to stretch the gas

ring 0.015” – 0.025” over the required length so the sharp

edge can be polished flat.

I

couldn’t use the stretcher on the cylinder with the shorter

gas ring because the gas ring kept coming out of the tool.

So, I decided to try the bushing method. I chucked the

cylinder in the 4-jaw chuck of my lathe and made sure it was

perfectly centered and flat. I used a 7/16” square end mill

to mill out the center of the cylinder toa depth of 1/2”. I

then turned a piece of stainless-steel to fit into the

hole. I first drilled a 1/4” hole in the center of the

bushing, then reduced the diameter until it fit into the

hole in the cylinder. I measured the length of the .45 Colt

cylinder that came with the gun, then faced off the bushing

until the overall length of the cylinder and bushing matched

the .45 Colt cylinder.

I cleaned

the bushing and bushing hole with acetone, then installed

the bushing with Loctite 609. Once the 609 cured I had a

permanent bushing that won’t come out.

So

now my two conversion cylinders fit their respective

Vaqueros perfectly with no end shake, and I don’t have to

chase after those little washers every time I disassemble

the revolver for cleaning. |