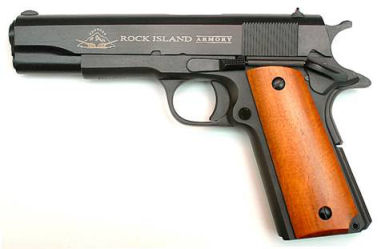

Fine-Tuning a Rock Island Armory M1911A1

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

If you have been keeping up with my articles you know I

wanted to get into shooting SASS® Wild Bunch matches based

on the movie The Wild Bunch. These matches require

large-caliber, big-bore guns; a lever-action rifle – my

Marlin 1894 cowboy in .45 LC will work, a Winchester 97 or

model 12 pump-action shotgun – I just finished modifying a

Winchester 97 (refer to my article

Modifying a Winchester 97 for Competition), and a

1911 .45 automatic pistol. I have two modern 1911 .45’s in

my gun collection, but I wanted to shoot traditional which

meant I needed a standard, G.I. pattern 1911 .45.

I found a

phenomenal deal on

Gunbroker for a new-in-box Rock Island Armory M1911A1

.45 for $330! One other person bid on it and raised the

price from $330 to $345; but it was still an excellent

deal. With shipping and transfer costs the total came to

$392, but Armscor was having a $50 rebate program at the

time so total cost to me was $342. If you can purchase a

1911 .45 for under $600 nowadays you are doing well, but

under $400 is a steal!

This is

the second Armscor Rock Island Armory 1911A1 I’ve owned.

The first one I purchased I gave to my son as a Christmas

gift. It had a number of problems; most of which I was able

to repair.

-

The

feed ramp was milled off-center in the frame. I

couldn’t fix this but it didn’t seem to affect the

feeding reliability of the gun

-

The

trigger pull was 10 pounds. I replaced the sear and

disconnector to get a decent trigger pull.

-

The

chamber in the barrel was undersized and would not

chamber ammunition. I had to ream out the chamber to

proper specifications to get ammo to chamber reliably.

Refer to my article

Reaming a .45 ACP Chamber.

By the

way, my son reports that he has never had any failures with

that gun, and all of his friends want to shoot it because of

the excellent trigger. You just can’t beat a 1911 with an

excellent trigger!

Armscor

makes a fine, functional handgun built to G. I.

specifications. But because they are mass produced nothing

is hand fitted and many of the parts still have rough

tooling marks from the manufacturing process. The manual

that came with the gun stated that the gun would need

approximately 500 rounds to break it in. That’s a lot of

ammo! The process of breaking-in a firearm is really

nothing more than shooting it enough so the parts will be

polished and wear-in together. I can eliminate much of the

break-in requirement by polishing the necessary parts and

areas myself. This will improve both the function and

reliability of the gun, not to mention saves on ammo.

Initial

Assessment

After I picked up the gun from my dealer I did a cursory

examination and function check. Everything worked as it

should and the trigger pull was actually decent at 4 1/2

pounds. The thumb safety required a hydraulic press to

operate (ok, I’m exaggerating, but my thumb is still sore

from trying to engage the thumb safety) but I can polish and

re-contour the edge that rides along the plunger to make

this easier to function. This gun came with the narrow WWI

front sight so I will have to install taller, wider sights

which are legal for a traditional gun.

I took

the slide off of the frame and found most of the mating

surfaces had milling and tooling marks left over from the

manufacturing process. These will have to be polished out

to facilitate reliability and smooth functioning.

Everything on this pistol was Parkerized, which meant they

all had a rough finish which will also need to be polished.

I wonder if WWI and WWII era 1911’s came off the wartime

assembly line rough like this. Perhaps they had to in order

to meet wartime production needs. These guns were designed

to function in the dirt, dust, and mud of war and were loose

out of necessity. Accuracy was “minute-of-enemy soldier”,

not bull’s-eye.

So am I

trying to make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear? Not really;

I just want to make a mass-produced handgun function

reliability. It’s not a target or tactical pistol, but it

is a competition pistol so it has to function reliably. I

don’t have to get all shots to touch at 25-yards; I only

have to keep a group to “minute of steel” accuracy. I have

built three 1911 pistols from scratch so I will apply many

of the polishing and fitting techniques I learned from the

late Dave Sample to this gun.

Slide

Work

I decided to start with the slide since this will require

the least amount of work. I completely stripped the slide;

removing all internal parts. Just so I only have to say

this once, when I exposed bare metal after polishing, I

applied cold blue to protect the metal.

Polish

the Slide

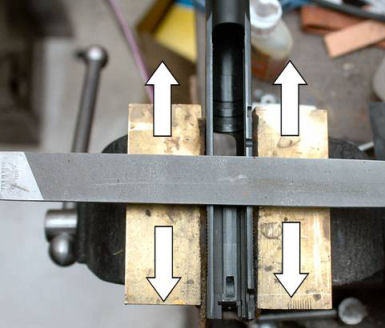

I placed

the slide upside down in my padded vise leaving about 1/4”

of it above the top of the jaws. I used a bastard file and

draw-filed the bottom of the slide rails to remove the

milling marks. Draw filing moves the file back and forth

90-degrees to the surface being smoothed as shown in the

above photo. This removes metal but doesn’t leave deep

filing marks. I was careful to keep the file flat so the

rails were nice and flat. I didn’t want to remove all of

the tooling marks since the slide was already loose on the

frame, just polish down the high areas. I finished

polishing with 400-grit wet/dry sand paper to complete the

process.

The small

rail where the disconnector and hammer ride had a lot of

tool marks so it too needed to be polished. I first used a

#0 Swiss pillar file I purchased from Brownells

#191-398-990 to smooth this area of the slide, being

sure to keep the file flat against the rail. I didn’t use a

lot of pressure on the file; I let the file do the work for

me. I completed the process with 400-grit paper to get this

surface smooth.

In order

to make it easier to feed a round from the magazine I

smoothed the breech face so that it shined and all of the

tool marks were removed. I used a 400-grit stone using very

light strokes, then finished with a 600-grit stone. Again,

I wanted the tools to do the work for me.

Working

the Barrel

Based on

my previous experience with a RIA gun I first checked the

chamber to make sure it was up to spec. I dropped a couple

of different reloads into the barrel and they chambered just

fine. I also dropped a .45 ACP go headspace gauge into the

chamber to make sure it fit. This chamber seems to have

been reamed correctly at the factory.

I

polished underneath the barrel where it sits in the barrel

bed of the frame, and the top of the barrel and barrel

hood. I shoe shined this area using 400-grit paper to get

it nice and smooth. I didn’t remove the tooling marks, just

made these two areas smooth by knocking off the high spots.

I used a

400-grit stone and smoothed the back and sides of the lower

lugs where they hit against the frame when the barrel

unlocks and drops down out of battery. This just needed to

be smooth, not pretty.

I used a

Cratex tip to polish the front of the lower barrel lugs.

These lugs ride against the slide release pivot pin so they

needed to be smooth. I was careful not to allow the bit to

slip or touch any areas other than the front of the lower

lugs.

At the

top of the feed ramp in the barrel throat is another sharp

edge I needed to bevel so cartridges will feed reliably. I

took the safe edge of a file (the edge with no teeth) and

scraped this edge back and forth to make a very slight

bevel, just enough to break the sharp edge. Then I polished

the entire throat with a Cratex bit.

Working

Slide Parts

All of the internal parts of the slide have to fit and

function together properly for reliability. I worked each

part individually which consisted mostly of polishing.

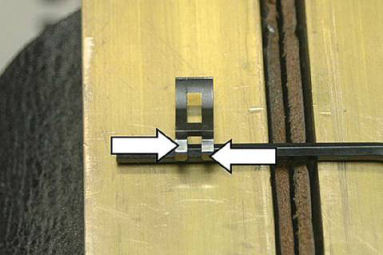

Checking

and Adjusting Extractor Tension

Tuning an

internal extractor is basically bending the extractor

(adjusting tension) until the extractor will hold a loaded

round. I completely installed all the parts in my slide and

inserted a loaded .45 ACP cartridge under the extractor hook

and against the breech face. On my pistol the cartridge

stayed in place as shown in the above photo indicating the

extractor tension was correct. If the cartridge did not

stay in place I would have had to adjust the extractor

tension.

The

proper tool for adjusting extractor tension is the Weigand

Extractor Adjusting Tool available from MidwayUSA

#931460 or Brownells

#957-000-037. This tool bends the extractor to add the

proper amount of tension to hold a loaded round in place.

My extractor did not need any adjustment.

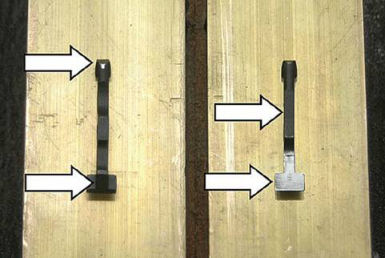

Fitting

the Firing Pin Stop

The

firing pin stop fit very tightly in the slide. This is a

good thing to prevent the firing pin stop from dropping out

of the pistol during recoil. However it required a punch to

remove and replace it in the slide. I laid the flat back of

the firing pin stop on a piece of 400-grit paper and

polished the rear until the Parkerizing came off. I tried

the firing pin stop in the slide and continued to polish

until I could insert and remove the stop with my fingers,

but it was still tight in the slide. I was careful not to

remove too much metal; it still needed to be tight.

Polishing

the Firing Pin

The

firing pin was binding inside the firing pin tunnel which

could cause misfires. I chucked the firing pin into a drill

and polished the front of the pin where it fits through the

firing pin hole, and the collar around the rear of the pin

where it rides in the tunnel. Now the firing pin moves

freely in the firing pin tunnel without binding.

Replacing

the Sights

As mentioned before this gun came with the narrow WWI front

sight. I wanted taller and wider sights for a better sight

picture. Rather than purchase new sights I fabricated my

own out of 1/8” flat steel bar stock. Although I have made

dovetail front sights before (refer to my article

Fabricating a Custom Front Sight) I wanted to

maintain the original staked-on front sight.

I found

some examples of taller front sights on the Internet that I

decided to copy. The front sight I chose to copy was 0.180”

tall as measured from the top of the slide. Jerry

Kuhnhausen states that the rear sight should be 0.035” –

0.045” higher than the front sight.

I chose the middle at 0.040”. Now for some basic math:

0.180” -

Front sight height above top of slide

0.180” +

0.040” = 0.220” - Height of rear sight above slide

0.09375”

– Depth of rear sight dovetail

0.220” +

0.09375” = 0.31375” – Total height of rear sight including

the base

0.125”

sight base – 0.050” depth of notch = 0.075” – Metal left in

sight base

0.31375”

Total height of rear sight – 0.075” = 0.23875” – Height of

rear sight blade

The rear

sight blade needed to be 0.23875” which I rounded up to

0.239”.

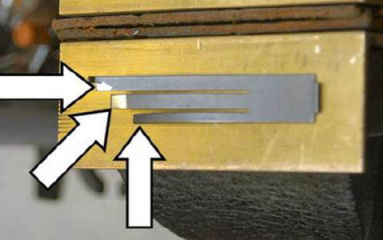

I milled

a 1/8” slot 0.050” deep in my 1/8” flat steel bar stock,

then cut out all of the parts. I used a small file to

remove any burrs and sharp edges. I squared the square

notch in the rear sight blade with a flat jeweler’s file;

the result was that the notch measured 1/8” (0.125”) which

is normal for target sights.

I tinned

the slot in the base and the bottom of the sight blade with

silver solder, then held both pieces in place with

vise-grips and heated them until the solder melted. I also

ran a bead of silver solder along the seam on both sides of

the blade so it would run into the joint. I allowed the

sight to air cool; cooling by using compressed air or water

can cause the silver-solder joint to become brittle and

weak. I took a flat jeweler’s file and removed any excess

solder from the base and blade.

I set the

blade in my machinist’s vise with the base up and used a

0.032” feeler gauge to level the base. The feeler gauge

ensured the base was not touching the top of the vise jaws.

I used a 65-degree sight base cutter I purchased from

Brownells

#080-621-495 and milled the dovetail angle on both sides

of the sight base. Because the cutter was made of high

speed steel I kept the speed of my mill to below 700 RPM per

Brownells instructions. I removed just enough metal so the

sight would just barely start in the dovetail. I used a

65-degree dovetail file I purchased from Brownells

#080-648-165 to finish removing metal so I could insert

the sight halfway into the dovetail with my fingers. I

finished tapping the sight in place with a brass punch. The

goal here is to make the sight easy to drift in the dovetail

slot to make windage adjustments, but tight enough so it

won’t move under recoil.

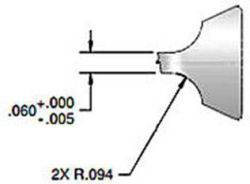

The

specifications for the rear sight call for a 0.094” radius

on the front and rear. 0.094” radius is 0.188” diameter

which is 3/16” or 0.1875”. With the rear sight in place I

put masking tape on the sides of the slide to prevent

marring the finish and leveled it in my machinist’s vise. I

used a 3/16” ball end bit to add the radius to the front and

rear of the sight and positioned it 0.005” above the top of

the slide. I milled each radius until I removed 0.032” from

each face of the sight blade. This allowed me to thin the

blade from 0.125” down to 0.060” as called for in the

specifications. I removed the rear sight, bead-blasted it

with glass bead media, cold-blued it, then reinstalled it

into the dovetail. It looks like it was factory produced.

Now for

the front sight. I removed the original front sight by

first using a pair of vice-grips and wiggling it back and

forth until it broke off of the stem. I was careful not to

mar the finish on the slide. I used a small punch to drive

the leftover stem out of the slide by punching it through

from outside to inside.

The

thickness of the new front sight measured 0.124”. The

narrow tenon needed to be 0.056” so I used my hobby CNC mill

to remove 0.034” from each side of the tenon. The new front

sight fit perfectly in the slot in the slide.

I

bead-blasted the sight using glass bead media, then

cold-blued the sight. You can see the result in the above

photo.

I applied

some green Loctite #609 to the tenon and inserted the sight

into the slot. I protected the sides of the slide with blue

painter’s tape and put the slide upside-down in a

machinist’s vise with the top of the sight touching the base

of the vise. I used a prick punch and steel 1/8” punch to

carefully peen and expand the end of the tenon until it

filled the bevel inside the slide. The bevel was deep

enough so I didn’t have to remove any excess peened metal so

the barrel bushing could rotate freely.

Here is

the gun with the new sights installed. If I did the math

correctly I should still be able to hit steel and be fairly

accurate. If not, I can always drift the rear sight, or

fabricate a new front sight.

Working

the Frame

The frame needed some polishing so parts would fit and

function together smoothly. Also since most of the parts

were rough Parkerized, they also needed to be polished to

work together smoothly.

Polishing

the Barrel Bed

I wanted

to polish the barrel bed where the barrel sets against the

frame when it is out of battery. When I started to polish

the bed I found two raised burrs at the end of the barrel

bed. These appeared to have been raised by something

striking the end of the barrel bed; probably the recoil

spring guide rod. I took my #0 narrow pillar file and

carefully knocked off these burrs.

I wrapped

some 400-grit paper around the top of the barrel, turned the

barrel upside-down and polished the barrel bed in the

frame. Again, I left a lot of the tooling marks behind; I

just polished down the high spots.

Re-Contouring the Hammer Spur

I am one

of those shooters that suffer from hammer bite. After

shooting only five rounds with my son’s pistol the web of my

hand was torn open. The hammer spur on the G.I. 1911 has a

thick, sharp edge at the bottom rear. I put a fine sanding

drum on my Dremel tool and thinned and rounded this edge. I

then polished with a Cratex bit and cold blued. Hopefully

this will eliminate the hammer bite.

Re-Contouring the Thumb Safety

As

mentioned before the thumb safety required an excessive

amount of force to engage and disengage. I used my Dremel

tool and a fine sanding drum to reduce the radius of the

front shelf of the thumb safety where it rides against the

plunger. I removed a little metal at a time and tried for

fit and function. When it functioned the way I wanted it to

I used a Cratex bit to polish that surface. Now I can

engage and disengage the thumb safety easily.

Adjusting

and Re-Contouring the Grip Safety

The grip safety was disengaging from the trigger almost at

the end of its travel. That meant I would have to grip the

gun tightly to disengage the grip safety. In the heat of

competition I may not always grip the gun the same way every

time so I wanted the grip safety to disengage earlier.

I filed

the bottom ledge under the front lobe of the safety until it

disengaged earlier in its travel. I took a few strokes with

a #0 narrow pillar file and tested the function frequently.

It still needed to function properly as a safety, but now it

disengages much earlier in its travel. I also beveled and

polished the sharp edges on the bottom-rear of the grip

safety. I didn’t want these edges to dig into my hand

during recoil.

Polishing

the Trigger Stirrup

I used my

Dremel tool and a Cratex bit to polish the sides and rear of

the trigger bow. This removed the rough Parkerizing and

made these surfaces smooth. I cold blued all exposed

surfaces after polishing.

(viewed

from the front)

The sear

spring has three leaves that needed to be polished. I

polished the front of the left and center leaves, and the

rear of the right leaf. These surfaces ride against the

sear, disconnector, and grip safety so they needed to be

smooth.

I

polished the front and back of the bottom of the

disconnector by rubbing these areas on 400-grit paper set on

a flat surface. I used a Cratex bit to polish the tip of

the disconnector. The sear and sear spring ride against

these surfaces so they needed to be smooth.

I also

polished the rear and bottom of the sear. The trigger bow,

sear, disconnector, and sear spring all rub together so they

needed to be polished and smooth to facilitate a smooth

trigger pull.

Hammer

Follow

After polishing the parts of the fire control group I

performed a test for hammer follow. I locked the slide

back, and with no magazine in place, pressed down on the

slide release and allowed the slide to slam into battery.

The hammer dropped to the half-cock position every time,

which is called hammer follow. This is caused by one or

both of two conditions; either the sear spring was too weak,

and/or the hammer and sear mating surfaces were cut

incorrectly.

To test

if the hammer and sear mating surfaces were cut incorrectly

I again locked the slide in the open position and held the

trigger depressed when I released the slide. This time the

hammer stayed in the full cock position meaning the hammer

and sear mating surfaces were correct.

I

disassembled the gun and bent the center leaf of the sear

spring forward to add more tension. This increased the

trigger pull to 4 3/4-pounds – still acceptable for

competition – but eliminated the hammer follow problem.

Function

and Fire Tests

I loaded one round in a magazine, loaded the magazine into

the pistol, charged the round and fired the pistol. The

empty case was ejected and the slide locked back as it

should.

Next I

loaded two rounds in a magazine, charged the first round,

then fired the pistol. I was looking to see if the gun

would double-fire or go full auto. This gun did not. I

fired the second round and the slide locked back as it

should.

Finally I

fired a full magazine to see if the gun functioned properly,

and it did. I think it’s now ready for competition.

Wild

Bunch Match October 25, 2014

I attended my first Wild Bunch match sponsored by the

Walnut Grove Rangers in Ellenboro, NC. We fired 105

pistol rounds spread over six stages. My RIA 1911A1

functioned flawlessly! I did not have any failure-to-feed

or failure-to-eject malfunctions. I had one reload that did

not have enough powder in it so it short-cycled the gun

causing a jam which I had to clear on the clock, but this

was the ammo’s fault, not the fault of the gun. More

importantly, the front sight did not shoot loose or come

off. I was a bit worried since this was the first time I

installed a front sight by staking it in place. I still

suffered from hammer bite; the web of my right hand had a

bloody blister by the end of the day, so I guess this is

something I will have to live with.

As for

accuracy the new sights allowed me to place the shots right

where I needed them to go. When I did my part I was ringing

steel all day. Believe it or not, I had two stages where I

fired the pistol clean, but missed a rifle or shotgun

target. Well, as they say, there is no target big enough,

or close enough that you can’t miss. By the way, I fired

traditional which meant I fired the gun one-handed. I came

in third place in the traditional category out of four

shooters, and placed 6th overall out of 12 shooters. Not

bad for my first Wild Bunch match.

Summary

I could have purchased a G.I. slide, slide parts, and frame

parts to convert one of my modern 1911’s into a G.I pattern

pistol, but purchasing these parts would have cost almost as

much as this entire pistol! Plus my two modern pistols were

all hand fitted so another slide might not fit properly. I

built a 1911 .22 pistol (refer to my article

Building a Dedicated 1911 .22LR Pistol) so I could

have purchased the parts to convert it to a G.I. .45, but

again the total cost of the parts would have been almost as

much as this RIA pistol. If the price of the gun had been

much above $400 it would have been cheaper to purchase the

parts, but now I have a complete pistol without having to

swap out parts.

Many of

the specifications I used to fabricate parts came from Mr.

Rio Benson of Benson Consulting, LLP. He developed a

complete set of technical drawings for the M1911-A1 pistol.

You can download the complete set of drawings by clicking on

the link below.

M1911 A1 Drawings

|