Building the Ultimate .22 Trail Gun

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

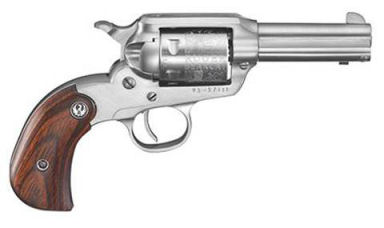

I read an article in the December, 2013 issue of American

Rifleman about gun distributor Lipsey’s

Guns commissioning a special production run of the Ruger®

new model Bearcat® called the Shopkeeper.

It was a new model Bearcat with a 3-inch barrel and

bird’s head grip in stainless steel.

I thought the idea of a small .22 revolver for camping,

trail, or tackle-box use was a great idea, but I didn’t want

to spend $650

to buy one, even though I’ve always wanted to own a Bearcat.

The author of the article also bemoaned the fact that

it didn’t come in .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR) better

known as .22 magnum, with which I agreed.

I also didn’t like the fact that it came only with

fixed sights.

I

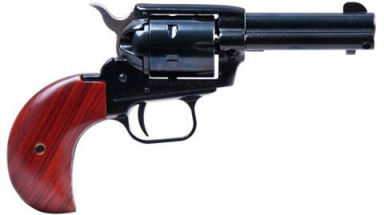

did some research on the Internet to see what else was out

there for .22 magnum revolvers and I found that Heritage

Manufacturing Inc. produces a .22 caliber convertible

revolver called the Rough Rider for about 1/3 the price of the

Shopkeeper. The

Shopkeeper only comes with one cylinder chambered for .22

long-rifle (LR), but the Rough Rider comes with two cylinders;

one for .22 LR that will also chamber .22 short and .22 long,

and a second cylinder that will chamber .22 magnum.

Although this fine, very affordable revolver came with

a bird’s head grip and short barrel, I decided not to

purchase one. The

finish was blue, not stainless steel – not good if you’re

going to throw it in a tackle-box and use it around water; it

had fixed sights – I prefer adjustable sights; and it had a

Colt action. This

meant that with all chambers loaded and the hammer down, the

firing pin would rest on a loaded cylinder creating an unsafe

condition, so in reality you could only carry five shots, not

six. Although it

also had a hammer block, I just wouldn’t trust carrying the

gun with all six chambers loaded.

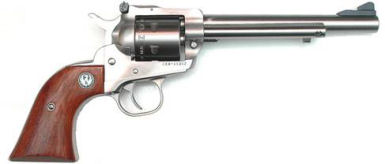

I

have two stainless steel Ruger new model Single-Six®

revolvers in my gun collection.

One is a “Liberty” gun manufactured in 1976 with the phrase, “Made in the

200th year of American

Liberty” engraved on the barrel.

The second one is just a regular model built sometime

in 2003. I had

originally purchased the second one to match the “Liberty” gun so I could teach a young person how to shoot cowboy

matches, but that never happened.

Since these guns have a transfer bar safety I can

safely carry them with all six chambers loaded.

These

guns both came with a 6 1/2-inch barrel and two cylinders; one

for .22 short, long, and long-rifle, and a second one for .22

magnum. I’ve

discovered over the years that when shooting .22 LR their

accuracy left something to be desired, but they shot .22

magnum very accurately. The

SAAMI bore diameter specification for .22 long rifle is 0.222,

but the bore diameter specification for .22 WMR is 0.224.

To prevent excessive pressure when shooting .22 magnum

the bore has to be a bit larger.

I slugged the bore on this project gun and it measured

0.223, which meant .22 LR bullets were a bit loose in the bore

so were not as accurate, but .22 magnum bullets fit tightly in

the bore which made them more accurate.

The

combination of stainless steel, adjustable sights, transfer

bar safety, and being able to shoot different types of .22

ammunition made this conversion a viable project.

The Shopkeeper is smaller and lighter than a

Single-Six, but I wanted the flexibility the Single-Six

offered.

Conversion

Plan

After reading the Shopkeeper article I decided to convert the

non-Liberty Single-Six into a trail gun by performing the

following:

- Set

back the rear sight

- Shorten

the ejector rod, ejector rod spring, and ejector rod

housing

- Cut

the barrel to 3 1/4-inches

- Shorten

the cylinder pin

- Install

a bird’s head grip frame

- Perform

an action job

These

changes would make the gun smaller, lighter, and easier to

carry, but obviously not as small nor as light as a Bearcat.

Also, the gun would be very usable for me, but could

also still be used by a “buckaroo” for cowboy action

shooting.

Setting

Back the Front Sight

I wanted to drill and tap the front sight and ejector rod

housing screw holes before I cut the barrel to ensure I had

enough barrel length to put into my milling vise.

The front sight is attached to the barrel with a single

6-40 screw, but I needed to make sure that when I marked the

barrel for the new screw hole, it was at the exact top of the

barrel.

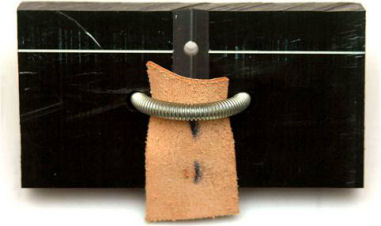

I

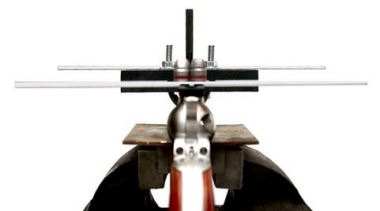

developed a tool out of a piece of polymer for marking the top

center of a round barrel.

The polymer block has a V-groove milled width-wise with

a hole in the center of the groove.

A U-bolt holds the block onto the barrel with a piece

of leather to protect the finish.

The white line you see on the bottom of the tool helps

me to align the hole properly along the length of the barrel.

I draw a line with a fine point marker down the side of

the barrel at the location of the sight screw and align the

white line with that mark.

I

placed an aluminum bar across the polymer block and a second

bar across the flat top of the frame over the rear sight.

Notice that I’m holding the rear bar in place with

two lead bullets. I

rotated the block until the bars were parallel, inserted a

center punch into the hole in the block and struck it with a

mallet. The

resulting center punch was perfectly centered at the top of

the barrel.

The

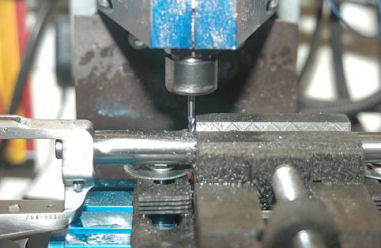

proper hole size for a 6-40 tap is 0.113”.

I used a 3/32” (0.09375”) square end milling bit

and my hobby CNC mill to mill the hole.

I measured the depth of the original hole at 0.150”

deep, but the screw only protruded from the bottom of the

front sight by 0.115” so I decided to make the hole 0.140”

deep. I placed the

barrel in my milling vise, centered the bit over the center

punch mark, and milled the hole.

I used plenty of cutting oil so I wouldn’t break the

bit.

I

replaced the bit with a 6-40 bottom tap and used vice grips to

start the threads. I

lubricated the tap with cutting oil and after every 1/8 turn I

backed out the tap to cut the chips. Once the threads were

started I removed the gun from the vise and used a tap wrench

to finish tapping the hole.

When the tap bottomed out I removed it from the hole,

then cleaned off all oil and metal chips with brake parts

cleaner.

Shortening

the Ejector Rod Housing

This

was probably the most difficult part of the conversion process

because of the round lip at the end of the housing that fits

into the frame. But

thanks to my CNC mill it was actually fairly easy.

There were three things I had to take into account when

calculating how much to cut; one - the ejector rod, spring,

and housing had to be long enough to touch the bottom of the

empty case and push it out of the chamber, two - the cylinder

pin had to be short enough to accomplish the same thing, and

three - the cylinder pin had to also be short enough and the

ejector rod housing long enough so I could pull the pin and

remove the cylinder from the frame.

I

cut the ejector rod housing to 2 3/4-inches which included the

1/8” lip. No

matter how hard I try I just can’t make a straight cut by

hand, so I cut the housing 1/16” longer so I could square

off the face. The

inside of the housing measured exactly 1/4“ so I inserted a

0.250” milling bit into the housing, then chucked it in a

1/4” collet in my CNC mill so I could get it centered and

square in my milling vise.

I used a piece of leather to prevent marring the

housing.

Once

the housing was secured in the milling vise I used the

0.250” square end bit to square off the end of the housing.

I milled down to the mark I made on the housing with a

blue marker. If

you look closely at the above photo you can see two blue marks

on the right side of the housing.

The top mark tells me where to stop squaring off the

end, and the bottom mark is the depth of the lip.

Next

I again used the 0.250” square end bit to mill the 0.306”

diameter lip 1/8” deep in the end.

After performing the milling the ejector rod housing

fit perfectly on the barrel and into the frame.

I could have performed this carefully with hand files

and achieved the same result, even though it would have taken

much longer.

I

installed the housing on the barrel and used a center punch to

mark the location of the mounting screw hole.

This hole needed to be 0.125” in diameter by 0.140”

deep to accommodate the 8-36 mounting screw.

I

placed the barrel into the milling vise with the mark up and

centered a 0.125” bit on the mark.

I ran my CNC mill to plunge-mill the hole, then I used

an 8-36 bottom tap to tap the threads.

The result is shown in the above photo.

It looks kind of weird because as I mentioned before I

wanted to set back the front sight and cut and fit the ejector

rod housing before cutting and crowning the barrel.

Shortening

the Ejector Rod and Spring

Now

that I have shortened the ejector rod housing, I needed to

also shorten the ejector rod and spring.

I installed the ejector rod into the housing without

the spring and installed the housing onto the gun.

The rod needed to be flush with the inside of the

frame. I marked

the rod and used my high-speed rotary tool with a cutoff wheel

to cut the rod, then I tapered and polished the end like the

original. I

measured the amount I cut from the rod and used wire cutters

to remove the same amount from the narrow end of the spring.

I had to cut 4 more coils off of the spring so when it

was completely compressed the rod would eject an empty case.

Cutting

the Cylinder Pin

Now

that I have a short ejector rod the cylinder pin was way too

long for the rod to even touch the head of the cartridge case

to eject it from the chamber, so I had to cut the pin, but I

couldn’t cut it flush with the frame, otherwise I wouldn’t

be able to remove it. The

factory pin had three grooves cut into it so I took my hack

saw and cut the pin at the middle groove.

I polished the cut end to remove the sharp edge and

teeth marks left from the saw.

Now the ejector rod ejects empty brass, but I

couldn’t pull the pin out of the frame far enough to remove

the cylinder. I

discovered this after I completed the gun!

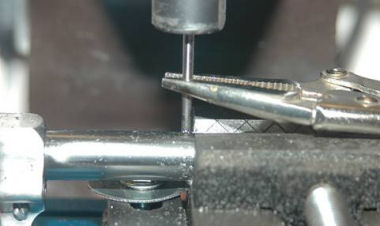

I

used a sharp scribe to mark where the cylinder pin touched the

ejector rod handle, then I used a long 1/4“ square end

milling bit to mill a notch in the handle as shown in the

above figures. I

used files and rubberized polishing bits to smooth out the

sharp edges and corners left from the milling process.

The

notch in the ejector rod handle allows the cylinder pin to

come back far enough so I can remove the cylinder, yet I left

the rear of the handle flat so my finger has a larger surface

to eject empty cases. The

Shopkeeper’s ejector rod handle is milled completely through

making a crescent handle, but I thought my solution was a

better compromise and unique.

Cutting

and Crowning the Barrel

This

turned out to be the easiest process of all because I had done

it before and had the correct tooling.

First I removed the front sight and ejector rod

housing. Then I

took a hacksaw and cut the barrel to 3 1/4“ plus 1/16”.

There’s nothing like the emotion of taking a hacksaw

to a perfectly good gun! As

mentioned before, I just can’t seem to make a straight cut

by hand so I cut the barrel 1/16” longer than necessary

which left me enough metal to square off the muzzle.

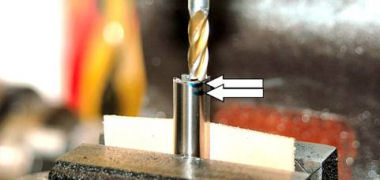

Next

I took my 90-degree facing cutter #080-586-

909 with a .22 pilot #080-943-211

that I purchased from Brownells and cut the muzzle square.

Next

I took a 1/2-inch 79-degree muzzle crown cutter #080-586-500

and cut a countersunk crown into the muzzle.

I placed a stop collar on the cutter to prevent the

cutter from chattering and cutting too deeply.

I

finished the process by lapping the muzzle with a .22 muzzle

lap. I put some

400-grit lapping compound on the end of the lap and while

running my drill at a slow speed less than 700 RPM pressed the

lap to the muzzle and rotated it in a circular motion.

This removed any burrs left over from the cutting and

crowning process. I

was explaining this process to one of my co-workers and he

wanted to know how I was going to remove the burrs left from

the cutting process. The

final lapping eliminates any nicks or burrs left from the

cutting, facing, and crowning process.

Cutting

the barrel cut into the factory engraving on the side of the

barrel which now detracted from the look of the gun.

I used a fine sanding drum on my high-speed rotary tool

to remove the engraving. You

can still see some of the engraving in the above photo.

I kept the drum moving up and down the length of the

barrel to prevent from leaving hollows and gouges in the

metal.

After

the engraving was removed I polished the barrel by

shoe-shining with 220-grit, then 400-grit wet/dry sand paper.

The above photo shows the result.

Fitting

the Bird’s Head Grip Frame

The stainless steel bird’s head grip frame I purchased from

MidwayUSA #821208

came oversized and rough cast so I had to fit it to my

existing frame, and do a lot of polishing.

This was the most time-consuming part of the entire

conversion process.

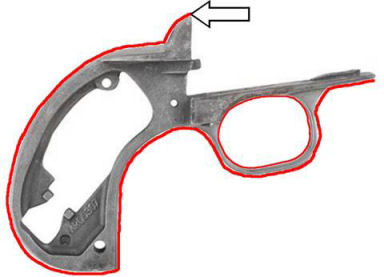

First

I used a fine sanding drum on my high-speed rotary tool and

polished all of the rough surfaces that would be final

polished. This was

the entire outside of the grip frame and inside the trigger

guard as shown in red in the above figure.

I again kept the drum moving along the length of the

metal to prevent leaving hollows or gouges.

Then I used the fine sanding drum to fit the curved

rear of the grip frame to the cylinder frame indicated by the

arrow. Finally I

polished all of the areas shown in red with 220-grit sand

paper. I made sure

to remove all sanding marks left from the sanding drum.

For the large areas I wrapped the sandpaper around a

piece of leather. For

small, hard to reach areas I wrapped the sandpaper around a

small file or piece of 1/4“ wooden dowel.

I finished polishing with 400-grit sand paper to get a

nice, smooth finish. For

the rounded areas like the front strap, back strap, inside and

outside of the trigger guard, I polished using a shoe-shine

motion. This was

to ensure I maintained the proper curves.

I

polished the sides of the trigger guard using 220-grit, then

400-grit sand paper wrapped around a narrow pillar file I

purchased from Brownells #191-400-760.

I wrapped the paper around the file to maintain the

flat surfaces of the trigger guard.

I

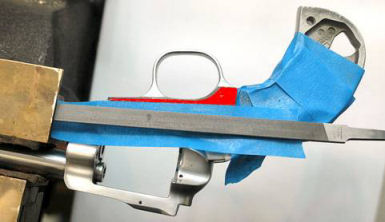

installed the grip frame onto the cylinder frame with the five

frame screws. I

taped both the frames to protect areas in case my file

slipped. I used

the narrow pillar file and carefully filed the edge of the

frame (shown in red in the above photo) until it just touched

the tape. This

meant I had about 0.003” left to be even with the cylinder

frame. I kept the

file flat and filed in one direction only.

I

wrapped a piece of 220-grit sand paper around the narrow

pillar file and finished blending the grip frame with the

cylinder frame. I

was careful not to touch the serial number.

Modifying or otherwise damaging the serial number is

against the law.

Once

the edge of the grip frame was even with the cylinder frame I

wrapped a piece of 400-grit wet/dry sand paper around the

narrow pillar file and finished polishing the frame.

I

performed the same process to side of the rounded rear of the

grip frame. I

again kept the file flat and filed in one direction only, then

finished with 220 and 400 grit sand paper.

The rounded rear of the frame side became flat, but I

gently rounded off the sharp corner with the file.

As you can see from the above photo the two edges mate

to the cylinder frame perfectly.

After

the grip frame was completely polished I bead-blasted both

frames, the loading gate, and ejector rod housing with glass

bead media to give them a soft, matt finish.

I could have given the gun a bright polish, but I

prefer the soft, matt finish for my trail gun.

Performing

an Action Job

When I purchased the “Liberty” Single-Six in 1977 the action was very smooth.

The Single-Six I purchased in 2003 was very rough!

My guess is with the increased demand for single action

revolvers Ruger could no longer spend the time to smooth up

the interior of the gun. I

spent a lot of time polishing the interior of the gun to get

it as smooth as the 1977 model, but I never performed a full

action job; all I did was polish the hammer and sear.

With the new bird’s head grip frame installed and the

original factory springs, the trigger pull measured 3

1/4–pounds, but was long with a lot of creep.

Usually

when I perform an action job on a Ruger single-action revolver

I replace the factory 23-pound hammer spring with a 19-pound

hammer spring, and replace the factory trigger return spring

with a reduced-power version.

Rim fire ammunition can be finicky so I decided to

leave the factory springs in place.

To

get a crisp trigger pull with no creep I first reduced the

length of the hammer engagement surface.

I installed the hammer in my Power Custom Series 2

stoning fixture I purchased from Brownells #713-270-014

using the universal adapter Brownells #713-271-000.

I used the original hammer pivot pin inserted groove

first into one of the holes in the adapter.

The pin was held in place by a set screw.

I made sure the set screw contacted the groove so as

not to raise a burr on the pivot surface of the pin. I marked

the front edge of the hammer notch with a blue marker and

adjusted the fixture until my stone was flat across the front

of the notch. The

notch in my hammer measured 0.022” so I took a 220 grit

stone and carefully reduced the depth of the notch to

0.014”.

I

then rotated the hammer so I could polish the engagement

surface of the hammer notch as shown in the above photo.

I marked the surface with a blue marker and made sure

to adjust the fixture so I was polishing this surface

perfectly flat. I

used my hard Arkansas stone with a beveled edge to

final-polish the surface.

Next

I installed the trigger in my Power Custom Series 1 stoning

fixture Brownells #713-070-008

using the BH (Blackhawk) adapter Brownells #713-070-008.

I used a blue marker to mark the surface and adjusted

the fixture until I was polishing the surface perfectly flat

and square. I used

ceramic stones Brownells #080-721-621

to polish the sear. I

used the coarse ceramic stone to polish off all of the

grinding/machine tool marks, then final polished with the fine

ceramic stone. Ceramic

stones use water as the cutting agent, not oil.

I

applied a bit of Action Lube Plus available from Brownells #083-050-002

to the hammer and sear mating surfaces to ensure smooth

function and to prevent corrosion.

I also applied the Action Lube Plus to all surfaces

were metal touched metal.

All other areas I lubricated with Breakfree CLP.

I re-assembled the gun and tested the trigger.

It broke at exactly 2 1/2-pounds every time with no

creep.

Making

Custom Grips

I decided I didn’t like the polymer bird’s head grips, and

besides they didn’t fit correctly, so I decided to make my

own set out of Brazilian blood wood.

Refer to my article Making Custom

Handgun Grips for additional details.

I

purchased a block of blood wood off of ebay.

The block measured 13 7/8” x 4 1/8” x 2 1/8”,

which meant I could cut 1/2“ slices off of the side to make

the scales I needed for my grips.

A scale is the block of material used to make a grip

panel.

I

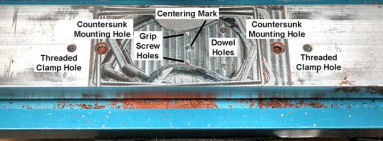

have a special jig that I made out of a 3” x 12” x 1”

piece of aluminum for making “plowshare” grips for Ruger

Vaqueros. This jig

holds the scale on my CNC mill for all of the milling

processes. I

discovered that the front edge, top edge, screw hole, and grip

panel dowel hole in the bird’s head grips were in the same

relationship as Vaquero plowshare grips so I had to make the

front and back of the grip match that relationship so I could

use the jig. There

are two grip screw holes, and two dowel holes in the jig to

hold a left and right grip panel in the proper orientation.

The centering mark helps me to center the jig in the X

(left-to-right) and Y (front-to-back) axes.

The two threaded clamp holes allow me to mount

adjustable clamps that hold the scale in place when milling

the screw and dowel holes.

First

I used CorelDraw v12 to make the outline of the grips.

The three small pieces to the left and right of the

outline are the profiles of the top edge, front edge, and tip

of the bottom. Once

I exported these into BobCAD-CAM I rotated these pieces

90-degrees to start the 3D shape of the grip.

I

exported the CorelDraw shapes into BobCAD-CAM v20 which I used

to produce the 3D model and CNC code for my Max NC 10CL hobby

CNC mill.

The

process of producing the grips was pretty straight forward:

Step

1: Cut the scale

to 2 1/8 x 4 1/8 x 1/2

Step 2: Mill the

screw and dowel holes in the inside of the grip panel

Step 3: Mill the

ferrule hole in the outside of the grip panel

Step 4: Mill the

outline of the grip

Step 5: Mill the

3D shape of the grip (this process took 3-hours per panel)

Step 6: Hand fit

to the grip frame

Step 7: Sand and

finish

I

designed the pattern to be just a bit oversized so I could do

the final fitting to the grip frame by hand.

Once the grip panel was completed and properly fitted I

sanded it with 180-grit sand paper to remove any leftover tool

marks from the milling process, 220-grit sand paper, 400-grit

sand paper, then finished with 600-grit sand paper.

I applied three coats of Birchwood-Casey® Tru-Oil®

allowing the grip to dry for 6-hours between each coat.

Summary

The Shopkeeper weighs in at 22 ounces as advertised, and the

Rough Rider at 33 ounces as advertised.

The factory Single-Six weighed in at 40 ounces but by

shortening the barrel, and changing to a bird’s head grip I

was able to remove 7 ounces so my trail gun now weighs in at

33 ounces, the same as the Rough Rider.

Both the Shopkeeper and Rough Rider didn’t meet all

of my requirements which are the reasons why I decided to

modify my Single-Six.

|