Modernizing a Winchester 37

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

About 20+ years ago a coworker approached me and wanted to

know if I was interested in purchasing an old single-shot

shotgun. I asked him if he had any details about the gun

and he told me that it was owned by his father which he had

inherited when his father passed away. I told him I would

be interested so he brought it into work (this was when we

could still do those things!) and we went out to the parking

lot so I could take a look.

It turned

out to be a single-shot, break-open 12 gauge Winchester

model 37 Steelbilt with a 30” full-choke barrel and an

external hammer. The Winchester 37 was manufactured from

1936 until 1963 and most did not have a serial number.

Because it was manufactured before 1968 it is legal to own

without a serial number. This gun is a classic piece of

Winchester workmanship. Who knows how much game this gun

has harvested over the years? It had a lot of surface rust

on the barrel from being stored under my coworker’s bed for

years, but some 000 steel wool and gun oil took care of

that. The receiver was starting to take on a plum color,

but other than those two issues, the gun was in excellent

condition. The bore was clean and bright with no pitting.

I used

this gun for trap shooting at one time, but I hadn’t used it

for years. Since I have been working on shotguns lately,

(refer to my article

Modifying a Winchester 97 for Competition) I decided

I wanted to modernize this old gun. My modernizing plan was

as follows:

-

Measure the chamber to make sure it would take modern 2

3/4“ shells. If not, then

-

Lengthen the chamber to take modern 2 3/4“ shells

-

Lengthen the forcing cone

-

Ream

and tap the barrel for interchangeable choke tubes

-

Replace the hammer

-

Replace the poorly-fitted recoil pad

-

Install a fiber-optic bead

-

Refinish the wood

Measure

the Chamber

Even

though the chamber was stamped for 2 3/4” shells, the

chamber gauge

#080-546-012 I purchased from Brownells would not fit up

to the 2 3/4“ mark. This meant the chamber was probably

designed for 2 3/4“ roll-crimp paper shells, not star-crimp

plastic shells. The forcing cone was also very abrupt so I

wanted to lengthen both the chamber and forcing cone.

Lengthen

the Chamber and Forcing Cone

A long,

gradual forcing cone can enhance the accuracy of a shotgun

because it doesn’t deform the shot so much. Since I also

wanted to lengthen the chamber to shoot 2 3/4“ plastic

star-crimped shells; I could perform both processes at the

same time with a long forcing cone reamer Brownells

#080-661-012.

I removed

the barrel from the receiver, then removed the extractor,

extractor guide, extractor sear and extractor spring from

the barrel. I installed the barrel in a padded vise with

the chamber up. I lubricated the long forcing cone reamer

with cutting oil and used a large tap handle to ream the

chamber and extend the forcing cone. Because the reamer had

straight flutes, when the flutes became full with chips, the

reamer became difficult to turn. I removed it from the

barrel always turning it clockwise to prevent breaking the

teeth, and cleaned off the chips. Each time I removed the

reamer I also cleaned the chips out of the barrel with brake

parts cleaner and checked the chamber with the chamber

gauge.

I stopped

reaming the chamber and forcing cone when the chamber gauge

fit up to the 2 3/4“ mark. I could have continued

lengthening the chamber to accommodate 3” shells, but this

gun was never designed for them so I stopped at the 2 3/4“

length.

To finish

the job I polished the chamber and new forcing cone with a

12-gauge chamber Flex-Hone® I purchased from Brownells

#080-608-512. This tool is a wire brush with abrasive

balls on the ends of the bristles and comes with a nine-inch

shaft. It should only be used with Brownells Flex-Hone® Oil

#080-008-609 to ensure the polishing is performed

correctly. I attached the hone to my drill and applied the

oil to the hone. I polished the chamber and forcing cone by

running the drill at a slow speed (<750 RPM) and moving it

in and out. I flushed the barrel with brake parts cleaner,

then oiled it with CLP. Now the chamber and forcing cone

are clean and polished smooth.

Ream and

Tap the Barrel for Interchangeable Choke Tubes

In order to ream the barrel for interchangeable choke tubes

the barrel had to be at least 0.845” thick. The barrel

measured 0.850” thick 1 1/2“ back from the muzzle. Cutting

the barrel at this point also removed the fixed choke, but

wouldn’t make all that much difference to the performance of

the gun. Before cutting the barrel I marked it 3 1/2-inches

behind the original bead with a center punch so I would know

where to drill and tap the barrel to move the bead. This

location would be behind the choke tube where the barrel was

nice and thick.

I have

done this process before on other shotguns; refer to my

articles

Threading a Shotgun Barrel for Choke Tubes and

Modifying a Winchester 97 for Competition for

details. After cutting the barrel I set it vertically in my

bench vise with the muzzle up and began reaming the barrel.

To facilitate the reaming process I put about 50-pounds of

bullets on top of the tap handle. I reamed the barrel until

the shoulder of the reamer squared off the front of the

muzzle. I used a rubber polishing wheel to round off the

sharp edge on the outside of the muzzle left from cutting

the barrel, then cold-blued the exposed metal. I then

tapped the barrel using the choke tube tap. I cleaned and

lubricated the new threads and installed a Winchoke® full

choke tube. Before installing the choke tube I lubricated

the threads with choke tube lube. This prevents the choke

tube from becoming stuck as the barrel heats up from firing.

I

purchased a 3-56 shotgun sight convenience kit from

Brownells

#078-021-256 that included a #45 drill bit, and a 3-56

bottoming tap. I used the #45 drill bit to drill a hole in

the barrel where I had marked it previously. To start the

tap perfectly straight in the new hole, I left the chuck of

my drill press centered over the hole, put the 3-56 tap into

the hole, then tightened the chuck just enough so the tap

would turn freely. I used a set of vise-grips to start the

tap about 2 turns; I reversed the direction of the tap after

every 1/4 turn to break the chips. After the tap was

started I used a small tap handle to finish tapping the

hole. I cleaned the hole and the threads of the original

silver bead with acetone, then applied a small bit of blue

thread locker and installed the bead.

Replace

the Hammer

This shotgun had a very small, curved spur on the hammer

(Winchester calls it a cocking lever) and the knurling was

worn almost smooth. It took so much thumb pressure to cock

the shotgun my thumb would be very tired and sore after

shooting a couple rounds of trap.

I found a

replacement hammer on

ebay, of all places, for $15.00 with free shipping.

That was cheaper than from

Numrich. If you notice in the above photo my hammer has

a thin curved spur, whereas the new hammer has a wide

straight spur. Although I can’t find any manufacturing

records for this gun, I’m guessing my gun was an early

production model. Customers probably complained about how

difficult it was to cock the gun so Winchester redesigned

the hammer with a straight spur. As a side note; a friend

of mine also has a Winchester 37 and his hammer has a wider

spur, but it is still curved, not straight. It seems that

this hammer went through a number of production changes.

After I

removed the butt stock from the receiver I could see that

two pins held the hammer in place. The top pin connected

the firing pin to the hammer, and the bottom pin was the

hammer pivot pin. I removed the two pins and withdrew the

hammer from the receiver.

The pivot

hole in the new hammer was too small for the original pivot

pin so I tried to ream it with a drill bit, but because the

hammer was hardened I broke the bit. I had to set up my

hobby CNC milling machine to mill the proper diameter hole

of 0.080”. I used a 1/16” square end bit and milled 0.0005”

deep each pass and kept it well oiled.

I

installed the hew hammer into the receiver and found that

the trigger sear did not fit into the ‘V’ notch in the front

of the hammer. I used my high speed rotary tool and a

cutoff wheel to expand the ‘V’ notch, then polished it with

a fine stone. The straight spur now makes the gun very easy

to cock and the trigger sear fits into the ‘V’ notch.

Replace

the Poorly Fitted Recoil Pad

(Photo courtesy of Hogue)

I

purchased a brown Hogue EZG grind to fit recoil pad size

medium

#00711 from the

eCop Police Supply web store on eBay. I purchased brown

because I thought it would nicely set off the refinished

stock.

Since the

pad measured one-inch thick I cut one-inch off of the butt

stock. I put two layers of masking tape around the stock

and cut it to the same angle of pitch. I don’t remember

where I read this, but somewhere I read that you need to use

a sharp saw blade to prevent splintering the wood. I

purchased a new blade for my table saw that cost $60, and it

not only cut the walnut like it was butter, but left no

splintering.

After

cutting the butt stock, I marked and drilled new holes for

the recoil pad. I mounted the pad onto the stock and

scribed a line around the stock. I have trouble seeing the

scribed line, so I filled it with white paint. I painted

the scribe line, then wiped off the excess paint with an

alcohol-soaked cloth. This made the scribe line stand out

so I could see it better. This worked so well that even my

errors and overruns showed up.

I then

sanded the pad using my modified jig and sanding table. For

details refer to my article

Installing a Recoil Pad. Every time I do this I get

better at it, and the white line really helped me from

sanding too far.

Installing a Fiber Optic Bead

My

Winchester 1300 Defender came with a slip-on fiber-optic

front sight. In reality it was a

Hiviz MPB sight. It slips on over the barrel, and a

V-notch in front sits against the bead which prevents the

sight from moving under recoil.

Since I

use an electronic holographic sight for my Defender, I took

the slip-on bead off of the Defender and put in onto the 37

barrel. As you can see from the above photo it sets back a

ways from the muzzle, but that green dot is big and bright!

Refinishing the Wood

The butt stock and forearm had a few dings and scratches in

them along with 70+ years of age. I wanted to steam out the

dents and generally refinish the wood. I removed the butt

stock from the receiver and the forearm from the barrel.

The forearm had one screw holding the mounting hardware in

place so I removed the screw and mounting hardware.

I used

Klean-Strip® KS-3 premium stripper I purchased from my

local home improvement store to strip the old finish from

the wood. This stripper is a thick paste which sticks to

the wood and doesn’t drip off. I applied the stripper with

a disposable brush and let it set for 15-minutes. I could

see the stripper start to work almost immediately. Then I

used paper towels to wipe off the stripper and the old

finish came with it. The above photo shows the forearm

before and after stripping. I performed the stripping

process three times to each piece of wood, then cleaned the

exposed wood with odorless mineral spirits as described in

the instructions. I was careful not to apply any stripper

to the inside of the forearm; I didn’t want to have to

refinish that area.

Once the

wood was stripped I applied a wet towel to the wood and

pressed a hot iron to the wet towel. This process steamed

out many of the dents, but also raised the grain. I could

not steam out some of the deeper dents and scratches, but as

my shooting friends say, that gives the wood “character”.

After the

wood dried I sanded the raised grain “feathers” with

400-grit sand paper until the wood was nice and smooth. I

applied some fast-drying polyurethane to the inside of the

hand guard and butt stock to help prevent moisture gathering

and causing rust.

I decided

to leave the walnut its natural color. I followed the

finishing video found on the

Boyds’® gunstocks web site using

Birchwood Casey® Tru-Oil®. This process takes some

time, but the results are outstanding. I applied six coats

of Tru-Oil and sanded with 1,000-grit sand paper after the

third coat. I have always liked the smooth, semi-glossy

finish Tru-Oil imparts to the wood as you can see from the

above photo.

Repairing

the Auto Eject

At the time I lengthened the chamber and forcing cone I

removed the auto ejector parts so they wouldn’t become

damaged. The four parts involved in the auto eject

mechanism were 1) ejector, 2) ejector sear, 3) ejector

spring, and 4) ejector guide.

When the

barrel is closed the ejector (1) rubs against the breech

face causing it to be pushed inward until the notch in the

ejector clears the ejector sear (2) hook. The ejector

spring (3) being under tension causes the ejector sear (2)

to rotate so the hook falls into the notch. The hook at the

top of the ejector (arrow) is positioned under the rim of

the shell, and the shell is now fully seated into the

chamber.

When the

barrel is opened and starts to swing forward the ejector is

still locked in place by the ejector sear. As the barrel

continues to swing forward the lobe on the front of the sear

(arrow) contacts the bottom of the notch cut into the barrel

hinge pin causing the sear to rotate so the hook drops out

of the notch. The ejector spring causes the ejector to

spring forward until it is stopped by the ejector guide (4)

causing the shell to eject out of the chamber.

The

barrel hinge pin is either pressed or silver-soldered into

the receiver so it cannot rotate. A notch is milled into

the center of the pin to accommodate the lobe on the front

of the ejector sear. The pin is installed so the notch is

at an angle to trip the ejector sear when the barrel is

opened.

On my gun

as the barrel was swung open, because the ejector was under

spring tension, the ejector was constantly rubbing against

the breech face and would open slowly. This allowed me to

pull the empty hull out of the chamber manually, but the

ejector would not snap open.

I

installed each part individually to make sure it moved

freely and found that the ejector sear was binding and would

not pivot. I polished the edges with 400-grit wet/dry sand

paper, and polished the ejector sear pin so the ejector

would rotate freely. I then installed the ejector, ejector

sear, and ejector guide without the spring to see how they

all worked together. After polishing the ejector sear and

pivot pin everything worked as it should. I lubricated and

reassembled the parts with the spring and now everything

works as it should.

Lightening the Trigger Pull

Although the trigger was crisp, it was very heavy. I

decided to lighten the trigger pull by replacing the trigger

return spring.

This

spring has a specific diameter to fit into a recess in the

frame to prevent it from slipping, and a specific length to

ensure the trigger spring guide rod stays in contact with

the trigger. This constant contact keeps the hammer back so

the firing pin does not protrude from the face of the

receiver to prevent loading or ejecting a shell.

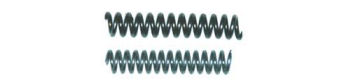

New Spring (bottom)

I didn’t

want to cut the original trigger return spring because I

couldn’t find a factory replacement spring or guide rod in

the Numrich catalog or exploded diagram, so I decided to

replace it. Again I believe this was an early production

model because none of the diagrams I found had the long

trigger return spring and guide rod. I never throw away a

spring; you never know when you might need one to fix

another gun. I cut a piece of 0.231” OD spring from

Brownells spring kit No. 71

#025-071-000 three coils beyond the length of the guide

rod. This lightened up the trigger pull to 5 1/4 pounds.

You can see that the new spring is made of a narrower gauge

wire and is one coil shorter which makes it lighter than the

original.

Summary

This was

a fairly easy project. Most of the modifications I performed with hand

tools. Although I used a drill press to drill and tap the

bead hole, I could have accomplished this with a hand

drill. I now have a 1930’s era shotgun modernized for the

21st century. Just for fun, I may remove the

fiber-optic bead and install a flush-mount choke tube and

use this gun for cowboy action shooting.

|