Making a Cartridge Check Gauge

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

If you shoot a lot like I do then you are probably also a

reloader. If you only shoot factory ammo then you either

donít shoot very often, or youíre in a higher income bracket

than I am. Shooting factory ammo has some advantages over

reloading; it is very reliable and very consistent. You

almost never have a failure to feed, failure to fire, a

squib or over-charged round with factory ammo. A squib is a

round that has little or no powder in it. When factory ammo

is fired through a chronograph the velocity often has a very

low standard deviation. Standard deviation is a statistical

value that shows how much variation or "dispersion" exists

from the average. The smaller the standard deviation value

the more consistent the load, which results in better

accuracy. A standard deviation value of 10 or less is

considered excellent for ammunition, and factory ammo often

reads way below this value. But for me I just canít afford

to throw 2, 3, 4 or more quarters downrange every time I

pull a trigger.

Reloading

is not only cheaper than purchasing factory ammo, but there

is a certain zen to the repetitive processes involved. With

reloads you can tailor your loads to your particular gun and

need, whereas with factory ammo what you buy is what you

get. However, reloaded ammo can have many problems

including those mentioned above.

Raised

Ring of Lead

Most semi-auto pistol cartridges use rimless cartridges

which headspace on the mouth of the case. Although it looks

like the case has a rim, this is actually the extractor

groove. When I first started reloading semi-auto pistol

rounds with lead bullets I quickly discovered a problem.

Most pistol caliber seating dies have a built-in taper to

apply a taper crimp to the case mouth. At the time the

crimp was applied the lead bullet was still being pushed

into the case which caused a ring of lead to be pushed ahead

of the case mouth. This problem did not occur with jacketed

bullets, and was a non-issue with revolver cartridges.

Chamfering the inside of the case mouth reduced this

somewhat, but it didnít eliminate it. The cartridge would

headspace on that ring of lead instead of the case mouth,

which prevented the slide from going completely into

battery.

This was

a constant problem for my lead pistol reloads until I

discovered the

Lee Precision factory crimp dies. Although this

requires a separate step, the case is crimped after the

bullet is completely seated so there is no ring of lead

causing the cartridge to headspace incorrectly.

Cartridge

Check Gauge

The final quality control step I perform to my hand-loaded

ammunition is to see if it will fit in the chamber of the

gun in which I plan to shoot it. This will find any bulged

or out or spec cases, or in the case of lead reloads for

pistol calibers, improper headspace caused by a raised ring

of lead. I do this by using a cartridge check gauge.

Whether

you know it or not, every gun comes with a built-in

cartridge check gauge; itís called the chamber! Revolvers

come with 5 or 6 chambers in the cylinder, and pistols and

rifles come with one in the barrel.

To use a

revolver cylinder to check loaded ammo I first measure each

chamber to find which one is the tightest. If my reloads

will drop into the narrowest chamber with no friction, then

they will fit in all the other chambers. If Iím using a

single-action revolver cylinder, I remove the cylinder from

the frame. If Iím using a double-action revolver Iím very

careful; safety first, last, and always. I drop the

loaded round into the tightest chamber and if it fits, I

remove it immediately and put it in my ammo box.

I DO NOT SWING THE CLINDER CLOSED

WITH THE LOADED ROUND IN THE CYLINDER. If I was to

close the cylinder I have now loaded the revolver, which

should never be done unless ready to fire. If the cartridge

does not seat completely in the tightest chamber, I set it

aside to rebuild it later.

For a

semi-automatic pistol I use the barrel as the chamber check

gauge. Most modern pistols allow you to remove the barrel.

I shoot a lot of .45 ACP so I use one of my 1911 barrels.

The process is the same; drop a loaded round into the

chamber; if it drops in without any friction, and sits flush

or below the barrel hood then it passes. If I am checking

cartridges in a pistol with a fixed barrel like a Walther, I

remove the slide and drop the cartridges into the chamber.

Again, if the cartridge fits with no friction and flush or

below the barrel hood the round passes.

EGW makes

a four-caliber cartridge check gauge available from

MidwayUSA product

#744135. Drop the reloaded cartridge into the

appropriate hole, if it drops in with no friction and fits

flush with the top of the gauge itís good to go. They make

one for revolver calibers as well.

L. E.

Wilson also makes a cartridge check gauge for many

individual calibers also available from

MidwayUSA. Type in ďcartridge check gaugeĒ in their

search field and you will see all of the choices available.

Making a

Cartridge Check Gauge

One of the potential problems I see with these stand alone

gauges is that the hole is not the same size as the chamber

of the gun in which the ammo is to be used. I decided to

make my own chamber check gauge for .45 ACP that would match

all of my .45 ACP chambers.

How would

I know the gauge would match all of my .45 ACP chambers?

Long ago I purchased a .45 ACP chamber finish reamer from

Brownells

#513-051-451. I used this reamer in all of my .45 ACP

barrels and cylinders to ensure all of the chambers were of

the same dimension. Back in 2011 I purchased a Rock Island

Armory M1911A1 as a gift for my son, but the slide would not

go into battery with most of my reloads, and even some

factory ammo. It turned out the chamber was way undersized

so I used this reamer to finish the chamber and bring it to

the proper dimensions (refer to my article

Reaming a .45 ACP Chamber). Using this same reamer

to make my gauge will ensure the rounds will fit in all my

.45 ACP guns.

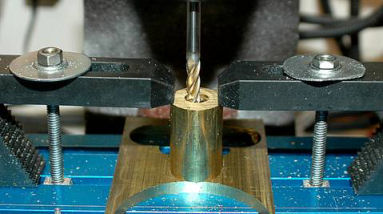

I

purchased a one-inch diameter brass rod 6-inches long from

OnlineMetals.com. I took a hacksaw and cut off a piece

1 3/8Ē long. I cut it just a little longer than it needed

to be because I canít make a straight cut freehand. I

mounted it in a machinist vise mounted to my table-top

milling machine and used a 1/2Ē square end milling bit to

square off the cut edge. The square piece of metal you see

below the brass rod in the above photo is a parallel. It is

cut perfectly square to ensure the piece Iím milling is

straight and square.

I marked

the center of the piece then milled a 0.4515Ē hole through

the center using a 0.250Ē square end milling bit. The front

of the chamber reamer measured 0.451Ē so I wanted the hole

to be just a bit larger so the reamer would turn, but not

wobble.

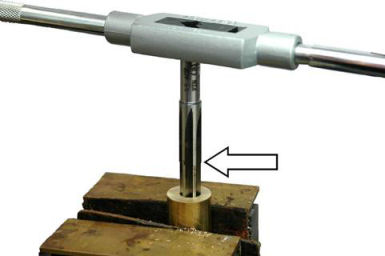

I set the

brass piece upright in a padded vise and used a large tap

handle to begin cutting the chamber. I made sure everything

was lubricated before cutting. Brass is much softer than

steel so I had to be careful I didnít cut too deeply. The

reamer was designed for a 1911 barrel; the lip in the center

of the reamer indicated by the arrow in the above photo is

meant to touch the barrel hood indicating the chamber was

cut to the proper depth.

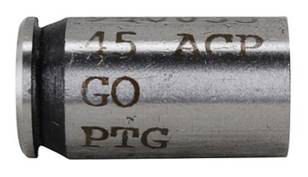

I marked

the reamer at the approximate position where I wanted to

stop reaming. When I got close to that mark I used a .45

ACP go headspace gauge to monitor my progress. When the

headspace gauge fit flush with the top surface of the brass

I was finished.

Now I can

take a couple boxes of reloaded ammo and an empty cartridge

box, sit in front of the TV, and check my reloads. If the

cartridge seats smoothly in the gauge, and sits flush with

the top, and it doesnít have a high primer which I check by

running my finger over it, I put it in the completed box.

If the cartridge doesnít seat smoothly and fully into the

gauge, or has a high primer, I set that round aside to

rework it.

Summary

Ok, so purchasing the reamer, the brass, and other tooling

is way more expensive than the $20 for the EGW or L.E.

Wilson gauges. But since my gauge matches all of my .45 ACP

chambers, I know if a cartridge fits in my gauge, it will

also fit in all of my .45 ACP revolvers and pistols. So why

not just spend the $20 for the EGW gauge and ream it with my

reamer? The 6-inch brass rod cost more than that. I plan

to use that brass rod for other projects so it was actually

cheaper to fabricate my own. The reamer has more than paid

for itself since I saved the labor of having a gunsmith fix

my sonís 1911 chamber and ream my other chambers. So all in

all I believe Iím ahead of the game.

|