Slicking Up a Pietta 1873 Single Action Revolver

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

When I first got started in Cowboy Action Shooting 15 years

ago I researched the guns I would need. The two most

popular styles of single-action six-gun revolvers were, and

still are, the Ruger Vaquero , and the Colt Single Action

Army (SAA) and its European clones. The Schofield revolver

wasn’t popular or readily available at that time, and since

the Vaquero was stronger and more robust than the SAA –

which was prone to breakage when used regularly for

competition – I decided to go with the Vaqueros. If you

read my articles you know that I am a Ruger single-action

man with Vaqueros, Blackhawks, and Single Sixes in my

collection, and I have many articles on how to modify and

improve the Ruger platform.

Recently

I’ve had a number of questions from readers of the Kitchen

Table Gunsmith regarding SAA’s and their clones. Having

never owned or worked on this style of revolver I decided I

needed to learn more about them. At the time I was

researching guns

Cabela’s was selling the Millennium revolver for $200.

This was a Colt SAA clone manufactured by

F.A.P. di Pietta Giuseppe & C. S.n.c. of Italy imported

by

Century Arms International. Although somewhat improved,

this same gun is still available today, now called the 1873

model. The price was very reasonable then, and 15-years

later the price was still reasonable, so I purchased two of

them in .45LC (my preferred caliber) from

WholesaleHunter.com, an online sporting goods outlet.

The price was so reasonable I could purchase two of these

Italian Colt clones for about the same price as one Ruger

Vaquero!

Personally I had no problem purchasing an Italian clone. I

have heard and read stories of the earlier clones being of

poor quality, but the Italians learned quickly that if they

wanted to compete in the American firearms market, and

especially with the

SASS® crowd, they needed to up their game. So much so

that these revolvers were named “Best Gun” by SASS® in 2002

and 2008.

Overall

Assessment

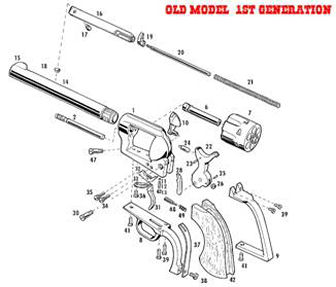

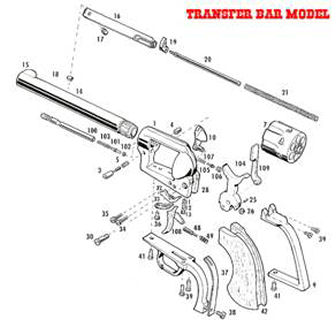

(Diagrams courtesy F.LLI PIETTA Srl)

After the

guns arrived I carefully examined them and gave them a

thorough cleaning. These guns are within six serial numbers

of each other so from now on I will refer to them as gun #85

and gun #91. I was a little disappointed that these were

not faithful reproductions of the Colt 1873 SAA. They did

not have the first safety notch click when cocking the

hammer because they came with a transfer-bar safety similar

to a Ruger. This meant I could safely load all six chambers

and not worry about having a hammer-mounted firing pin rest

on a live primer. The firing pin was mounted in the frame

and not on the hammer. Also, instead of having a flat hand

spring like an original Colt they had a coil spring and

plunger again similar to a Ruger. I feel as though I

purchased two “Col-gers” (a Colt/Ruger hybrid). Pietta made

safety and reliability improvements to the old 1873 pattern

by using a transfer bar and coil spring and plunger for the

hand.

The

finish was matte blue; they feel almost like they were

Parkerized. The action of each revolver, being brand new,

was stiff and the triggers broke at 2.8 pounds for each

gun. However, the trigger pull was long with a lot of creep

indicating that the sear ledge on the hammer was too deep.

I also

discovered that the hammer spring was so stiff that while

speed-cocking the revolvers like I would during a cowboy

match I sometimes didn’t get the hammer fully cocked so when

my thumb slipped off of the hammer spur the hammer dropped

into the half-cock notch. The half-cock notch helps to

prevent the dreaded “skipped round” but does cost time on

the clock. A reduced power hammer spring should fix this

problem.

I found a

couple of articles on the Internet (links below) on how to

improve the action of a SAA clone, plus I have two books in

my library on how to work on these revolvers, so these

references were the starting point for my work.

http://www.hobbygunsmith.com/Archives/Oct04/Interview.htm

http://www.gunblast.com/JimTaylor_Uberti.htm

Tools and

Parts

Most of

the tools, parts and supplies I purchased from

Brownells unless otherwise noted. After purchasing the

guns I purchased a set of screwdriver bits made specifically

for the Colt SAA and clones

#080-000-086, a Wolff reduced power bolt and trigger

spring

#969-322-900, and a Wolff reduced power hammer spring

#969-322-800. The screwdriver bits will help prevent me

from buggering up the screw heads when disassembling and

reassembling the guns, and the reduced power springs will

lighten the action and trigger pull.

Many

years ago I purchased the

Gunsmith Action Set of polishing stones from

Boride Engineered Abrasives. I have used these

excellent stones for many years on many guns; these are some

of the best tools I own for stoning gun parts.

By the

way, I never replace springs until AFTER I perform polishing

and function checks. I had a Ruger Vaquero that would no

longer function with a reduced power trigger return spring

because the trigger was rubbing against the frame. I had to

open up the cutout in the frame so the trigger would

function properly with the reduced power spring.

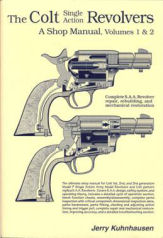

I also

purchased The Colt Single-Action Revolvers, A Shop Manual

Volumes 1 & 2 by Jerry Kuhnhausen from MidwayUSA

#133799. I have a number of Jerry’s excellent books in

my library and have found them to be a very important source

of information when working on guns.

Barrel

and Chamber Throat Measurements

I slugged the barrel and measured the chamber throats in

each gun. The bores measured 0.452 which is what I

expected, and the chamber throats measured between 0.452 -

0.4535. Since some of the throats were right at 0.452 I

decided to open them up just a bit.

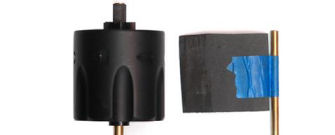

I

purchased a chamber throat reamer

#513-000-001 that opens the chamber throats to 0.4525.

It came with a pilot bushing so the reamer stayed centered

in the chamber. I have used this reamer to open the chamber

throats in all my .45 LC revolvers.

I

attached a T-handle to the reamer, lubricated it with

cutting oil, and ran the reamer through all the chambers in

both cylinders. I inserted the pilot bushing into the

cartridge end of the chamber until it met with the throat,

then I turned the reamer by hand until the teeth came

through the end of the cylinder. I flushed the chamber with

brake parts cleaner to remove any oil and leftover chips,

then lubricated each chamber with gun oil. For most of the

chambers the reamer fell through and performed no cutting.

The reamer shaved metal from only two chamber throats, the

ones that measured 0.452.

I am a

big fan of Ruger revolvers, but every big-bore Ruger I have

ever worked on had the same two problems; the chamber

throats were undersized, and there was a constriction inside

the barrel under the barrel threads. These two conditions

are detrimental to accuracy and require some work to correct

(refer to my article

Accurizing the Ruger Single-Action Revolver.) It

seems more care was given by the Italians during their

manufacturing process than one of the largest American

firearms companies! My two Pietta 1873’s had no barrel

constriction, and chamber throats were the proper size.

Disassembly

Disassembling the Colt single-action revolver is pretty

easy. Always use hollow-ground screwdriver tips of the

proper size to prevent from buggering the screw heads.

These photos and write up are for gun #91, but I performed

the same work to both revolvers.

|

|

Make sure the revolver is unloaded! |

|

|

Place the hammer in the half-cock position and open

the loading gate. |

|

Press in the base pin latch and pull out the

cylinder base pin. Remove the cylinder from the

right of the frame.

Close the loading gate.

Hold the hammer back so the trigger is out of the

loading notch, press the trigger, and allow the

hammer to move to the fully forward position and

rest against the frame. |

|

N/A for one-piece grips |

Remove the grip panel screw and remove the two grip

panels. My guns had one-piece grips so I did not

have to perform this step. |

|

Remove the three screws from the back strap; two

from the top and one from the bottom. The bottom

screw is a different size from the two top screws;

do not get them confused. Set them aside in a small

container so you don’t lose them.

Notice the hand spring that is exposed when the back

strap separates from the frame. |

|

With one-piece grips; rotate the back strap and grip

back and down to remove it from the trigger guard.

With two-piece grips; remove the back strap. |

|

Remove the hand spring and plunger from the rear of

the frame. Your revolver may not have this feature. |

|

Remove the hammer spring retaining screw and remove

the hammer spring. This screw was installed with

Loctite by the factory so it was very tight on my

two revolvers. I was sure to use the proper size

screwdriver blade/bit. |

|

Remove the three screws from the trigger guard and

remove the trigger guard. The front screw is

smaller than the two rear screws so don’t get them

confused.

This exposes the bolt and trigger return spring and

retaining screw inside the bottom of the frame. |

|

Remove the bolt/trigger return spring retaining

screw and remove the spring. This screw was

installed with Loctite at the factory so it was very

tight on my two revolvers. I was sure to use the

proper size screwdriver blade/bit. |

|

Remove the three screws from the side of the

frame. The trigger and transfer bar, hammer and

hand, and bolt can now be removed from the bottom of

the frame.

If you have the old-style hand with a flat spring

attached you will have to lower the hammer through

the bottom of the frame to remove the hand and

spring. |

|

Remove the loading gate detent plug screw from the

bottom of the frame, then remove the detent spring

and plunger.

Remove the loading gate from the frame by pulling

forward. |

Polishing

the Bolt

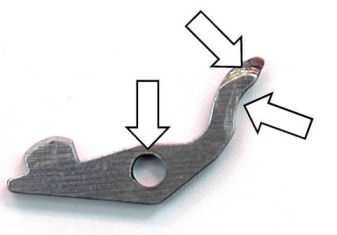

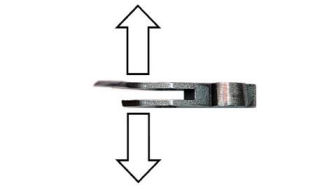

To my

surprise I found the right leg of the bolt had been cut off

to accommodate the transfer bar. There were some burrs left

when the leg was cut which I polished off using a 400-grit

stone.

The sides

of the bolt had tooling marks and burrs around the pivot

hole. I polished the sides of the bolt with 600-grit

wet/dry paper. The goal here was not to alter the

dimensions of the bolt, just polish off the burrs. I used a

Cratex bit and my high-speed rotary tool to polish the curve

and tapered end that ride on the bolt cam.

After I

reassembled the gun I discovered the bolt would not stay

down when the hammer was in the half-cock, loading

position. The curved leg of the bolt was slipping off of

the cam on the hammer causing the bolt to fall too early.

Upon inspection I found the long leg was a few thousands of

an inch away from the cam. I carefully pressed a large,

flat-blade screwdriver between the two legs to spread them

apart just enough so the long leg was laying flat against

the edge of the hammer so the cam was making positive

engagement. Now the bolt worked the way it should.

Just so I

only have to write this once, after I polished areas that

were blued, I re-blued with cold-blue to protect the exposed

metal. I first cleaned the part with brake parts cleaner,

degreased with acetone, then dipped the part in

Van’s Instant Gun Blue or

Birchwood Casey Perma Blue. I then coated the part with

gun oil to preserve and lubricate it.

Polishing

the Hammer

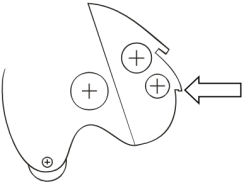

As you

can see from the above photo the hammer has no safety notch

because the gun has a transfer bar. I used a Cratex bit to

polish the cam that the bolt rides over and the front edges

of the hammer where the trigger rides.

The pin

that holds the hammer spring roller protruded from each side

of the hammer. I used a 400-grit stone to polish the ends

of the pin so they were flush with the sides of the hammer.

The hammer on gun #91 did not have any other burrs or

imperfections so other than dressing the sides of the hammer

where it rode in the frame, I performed no other polishing.

Caution: The following procedure requires special tools and

jigs to maintain the proper angles of the trigger and sear

and should not be performed without them.

The sear

ledge on the hammer for #91 measured 0.034-inch which

created a long trigger pull with a lot of creep. I placed

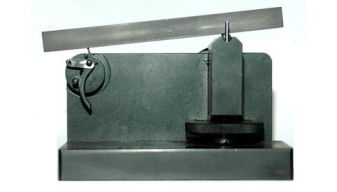

the hammer in my Power Custom Series 2 stoning fixture that

I purchased from MidwayUSA.com

#411263 using the universal adapter and used a 400-grit

stone to reduce the depth of the sear notch. I reduced it

to 0.020-inch and tested it for creep and let off. There

was still just a bit of creep left in the trigger but I

decided to leave it alone.

Once the

depth of the sear was set I polished the face of the sear.

I discovered that the Pietta hammer had a shelf that the

trigger rode on. When I reduced the depth of the sear I

removed that shelf.

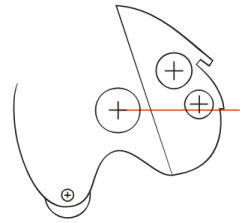

I rotated

the universal adapter and adjusted the fixture so I was

polishing the sear flat and at the proper angle. The angle

of the sear should be in line with the center of the hammer

pivot hole as shown in the above diagram.

I first

polished with the Power Series II India stone

#080-815-000 until the sear was smooth and shiny. I

then finished polishing with the Power Series II Hard

Arkansas stone

#080-815-001.

Polishing

the Trigger

The hole

in the trigger where the transfer bar rotated had some burrs

so I used a 400-grit stone to remove those burrs. I also

polished the back side that rubs against the hammer. There

was a burr around the trigger pivot hole so I stoned that

down as well.

The

surface of the trigger that mated with the sear on the

hammer was very rough and had visible tooling marks as you

can see from the above photo. I mounted the trigger in the

MKII adapter for my Power Custom Series 1 stoning fixture I

purchased from MidwayUSA

#743549. I didn’t have the Colt Single Action adapter,

but the trigger fit in the MKII adapter perfectly.

I coated

the trigger engagement surface with a blue marker and

adjusted the jig until my fine ceramic stone

#080-721-604 was polishing the surface flat. I polished

until all the tooling marks were removed. I finished with

the extra-fine ceramic stone

#080-721-601 to get a very smooth surface.

After

reducing the depth of the sear, and polishing the trigger

and sear the trigger broke cleanly at 2.1 pounds with just a

hint of creep.

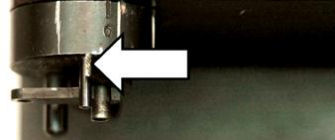

Polishing

Pivot Pins

The bolt

and trigger pivot screws were very rough so I chucked the

screw heads in my cordless drill and used 600-grit wet/dry

paper to polish them. I didn’t remove all of the tooling

marks because this would alter the diameter of the pins, but

I polished just until they were smooth and there were no

rough edges. You can see the bottom screw is much rougher

and more pitted than the top screw.

I chucked

the cylinder base pin in my cordless drill and polished it

with 600-grit wet/dry paper. The pin had tooling marks left

over from the manufacturing process and I wanted to smooth

them down just a bit.

I taped a

piece of 600-grit wet/dry paper around a 3/16 piece of brass

rod and ran this in and out of the cylinder base pin hole.

This polished out any burrs which allowed the cylinder to

rotate much more smoothly.

I

carefully polished off any burrs from the cylinder ratchet

on the rear of the cylinder, and the gas ring on the front

of the cylinder with a 400-grit stone. I only polished

these areas; I didn’t want to remove any metal otherwise I

would increase end shake which would also affect headspace.

Replacing

the Hand Plunger Spring

I felt

the hand plunger spring was way too strong so I replaced it

with a piece of 0.012 spring from Brownells spring Kit #69

#025-069-000. I cut the spring to the same length as

the original and pinched one end so it would fit over the

end of the plunger. The spring still provides tension to

keep the hand in contact with the ratchet on the cylinder,

but the cylinder now rotates much easier.

Reassembly

Throughout the polishing process I reassembled and

disassembled the gun many times to test for fit and

function. Now that everything was polished and fitted,

exposed metal was cold-blued, and the gun functioned

correctly it was time to reassemble the gun for the last

time.

As I

reassembled the gun I lubricated all parts that rubbed

together with Brownells Action Lube Plus

#083-050-002. This is a synthetic grease that I use for

the internal moving parts on all my firearms. I applied

small amounts of the grease using a toothpick to pivot

points and the trigger and sear. I also applied a touch to

the end of the hammer spring where the roller rides, and the

ends of the trigger and bolt return spring where they ride

against the trigger and bolt.

The leaf

of the bolt/trigger spring that rests on the trigger and

acts as the trigger return spring I bent up until it was

just touching the trigger. I tested it to make sure

the trigger would still function correctly.

I

discovered while dry-firing both revolvers that the frame

screws became loose. This would not be good, especially

during a cowboy match. As I reassembled the gun I cleaned

each threaded hole and corresponding screw with acetone,

then applied a drop of

Loctite Blue 242 to the screw threads. A little goes a

long way so if it looked like I applied too much; I touched

the end of a cotton swab to the drop to soak up the excess.

Primer

Test

My final test was to prime six .45 LC cases with CCI #300

large pistol primers, but no powder or bullet. CCI primers

are harder than other brands of primers, so if the gun will

pop CCI primers I should have no misfires. I loaded the

primed cases into the cylinder and they all fired with no

problems.

Summary

I

performed all the same procedures to gun #85 so now both

guns are competition ready. I now know more about the Colt

action than I did before, and I have two more cowboy guns

that I can use, or loan out to friends who come along to a

match with me. These guns were almost ready to go right out

of the box, even though all the screws needed some Loctite, but a little polishing and tweaking never hurts

to improve performance.

|