Cleaning Up a 1947 Marlin® 39A

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

Ever since I can remember I have been fascinated with

firearms. Unfortunately,

since my parents were not outdoors people nor sportsmen, my

exposure to shooting was limited to the high school rifle

team. On my 21st

birthday I purchased a .357 magnum revolver which began my

journey into the world of shooting and firearms.

One

of the guns I’ve always wanted to have was the Marlin®

39A lever-action .22 rifle.

Believe it or not, this desire began with an arcade

game. As a

teenager I used to play a shooting gallery arcade game that

simulated shooting bottles with a lever-action rifle.

I always thought that would be fun to do in real life

so I started researching lever-action rifles.

At the time I did my initial research, lever-action

rifles mostly came in .30-30 or .22 calibers.

The .30-30 was primarily used for hunting and would be

too expensive for plinking (I wasn’t reloading at the time)

so I concentrated on .22’s.

The one that kept coming up was the Marlin® model 39A.

The

Marlin® 39A has been in continuous production longer than any

other rifle in

America

, beginning in 1891. Annie

Oakley used one for her exhibition shooting.

Rather than being made of aluminum and plastic, this

rifle is all blued steel and American black walnut.

Its 24-inch barrel and full length magazine tube allows

me to load 26 short, 21 long or 19 long rifle cartridges.

Plus, I’ve always thought the takedown capability was

very convenient, and also pretty cool.

This rifle was always more expensive than other .22s on

the market, so over the years I’ve made do without a 39A.

Recently

on Gunbroker.com I

found a used, Marlin® 39A for $380; about twice the price for

a new Brooklyn-made lever-action .22.

Prices for new and used 39A’s were running $475+ so I

felt this was a good deal.

However, the fact that this rifle was built in 1947 (as

indicated by the prefix letter D in the serial number), it did

not have a hammer-block safety, and it came with a tang peep

sight made this an outstanding

deal in my estimation!

Initial

Assessment

This rifle appeared to be in great shape.

There were some dings in the butt stock and forearm but

these could be steamed out.

The metal and bluing were in excellent condition with

just a bit of surface rust and a few dings and scratches,

typical of a 60+ year old rifle.

It was also very dusty indicating that it had been

sitting around for some time.

There’s really no way of telling how many rounds have

been fired through this rifle, but the action was glass

smooth, and after a thorough cleaning, the bore looked bright,

and the rifling sharp. This

was not the light, aluminum and plastic lever-action .22 I was

used to. Instead,

this rifle felt heavy and solid; just like my other big-bore

Marlin® lever rifles.

Magazine

Tube

As with any used gun that I purchase, I completely

disassembled the rifle to give it a thorough cleaning and

inspection. The

first problem I found was with the inner magazine tube

assembly. It had a

slight bend about six inches up from the follower, and the

retaining pin that held the knurled plug in the tube was too

loose. This inner

magazine tube assembly was made out of aluminum, not brass,

and there were grinding marks on the tube where the retaining

pin holes were drilled which made me think it was a

replacement. Research

on the Internet indicated that this year gun came with an

aluminum inner magazine tube, so the replacement was period

correct.

I

disassembled the inner magazine tube and inserted a wooden

dowel so I wouldn’t over-bend the tube.

I gently applied pressure on the bend which was easy to

see because it was rubbed shiny.

I was able to get the tube fairly straight so it slid

easily into the outer tube.

I’m wondering if this was done on purpose to prevent

the tube from falling out, or sliding back in when loading

cartridges into the outer tube.

I took a cleaning rod with a .45 caliber cleaning patch

and thoroughly cleaned the inside.

It took about 6 patches to clean 60+ years of gunk,

then I ran a lubricating patch through the tube.

I

reassembled the inner magazine tube and tried to replace the

solid retaining pin with a roll pin but the hole was too

large. A larger

roll pin would not fit in the notch in the outer magazine

tube, so I installed the retaining pin and staked it in place

with a prick punch. To

finish my fix I put a 5/16” O-ring in front of the knurled

plug, which provided just enough tension to prevent the inner

tube from falling out.

Re-Crown

the Muzzle

As

shown in the above photo, the muzzle crown was rough and

pretty dinged up. A

poor muzzle crown will affect accuracy. I

decided to re-crown the muzzle, not only to make it look

better, but to also allow for maximum accuracy.

A

professional gunsmith uses a lathe to cut a new crown, but I

don’t have a lathe. I

used a 79-degree crown cutter I purchased from Brownells to

cut the crown by hand. This

cutter makes a recessed target crown, but I used a 1/2-inch

diameter cutter – smaller than the diameter of the barrel

– so I wouldn’t cut out to the edge of the barrel.

I installed the .22 pilot, handle, and a 1/2-inch stop

collar onto the cutter. The

stop collar makes the cut smooth, rather than uneven with

chatter marks. In

the photo above the stop collar is set back to show the

cutting teeth. I

adjusted the collar so it was almost flush with the front of

the cutter.

I

lubricated the pilot and cutting teeth with cutting oil and

turned the cutter clockwise.

I turned the cutter only in one direction; otherwise I

could break the teeth. I

cleaned chips off of the cutter and muzzle and lubricated the

cutter frequently. I

cut until the stop collar touched the front of the barrel.

You can see the nice, clean muzzle in the above photo.

After

I cut the new muzzle crown I used a brass muzzle lap to

final-lap the muzzle. This

ensured the lands and grooves were nice and sharp at the

muzzle which results in improved accuracy.

I took the smallest brass muzzle lap and chucked it in

my hand drill. I

put some 400-grit lapping compound on the end of the lap, and

with the drill running at a medium speed, I pressed the round

end of the lap against the muzzle and used a rotating motion

with my wrist to ensure the muzzle was lapped evenly.

Cutting

the new crown left a sharp edge on the front of the muzzle.

I took a 400-grit stone and went over that edge just

enough to smooth it down.

Finally, I blued the exposed crown with cold blue to

prevent the metal from corroding.

I degreased the crown with acetone, plugged the bore,

then immersed the muzzle in Van’s

Instant Gun Blue for about 5 minutes.

I wiped off the excess bluing solution, then treated

the metal with gun oil to stop the bluing process.

The above photo shows the result.

Trigger

I

didn’t really measure the trigger pull before starting this

project, but I did want it lighter.

To reduce trigger pull first I replaced the hammer

spring. I removed

the original hammer spring by pushing the top of the

mainspring plate to the right until it slid out of the frame.

I installed a Wolff

reduced power hammer spring that I ordered from Brownells.

In the above photo you can see the original hammer

spring next to the installed Wolff spring.

To

further lighten the trigger pull I pulled up on the trigger

return spring until it made light contact on the trigger.

After reassembling the rifle the trigger measured 2 1/2

pounds, and the rifle was easier to lever.

I pulled the bullets and powder from various .22’s I

had to test if the lighter hammer spring would still pop a

primer. Of the

three different types of .22’s I tested, the rifle fired the

priming compound with no problems.

If you notice in the above photo there are two notches

in the bottom of the receiver for the mainspring plate.

If the replacement hammer spring was not strong enough

I could have used the forward notch thereby increasing spring

tension.

Rear

Sight

This rifle came with a fixed, non-folding, rear sight.

I removed the rear leaf sight by drifting it out of the

dovetail from left to right.

I don’t really need two sights installed, and the

leaf sight got in the way of the peep sight.

I

ordered a Marble Arms®

replacement folding rear sight from Brownells #579-000-082 and

installed it from right to left in the existing dovetail.

This sight does not use an elevator to raise the sight;

rather there is a blade insert that slides up or down in a

channel and is locked in place with a screw.

The insert has a white diamond and has two different

notches, round and V; I used the V.

Plus, this sight is also windage adjustable.

Now I have the tang peep sight as my primary sight, and

the folding leaf sight as a backup.

I keep the leaf sight folded down when using the peep

sight.

Front

Sight

The front sight blade came with a brass bead, but as I get

older I have trouble seeing that little tiny bead, even after

polishing it up with a drop of Brasso®

on a cleaning patch. I

decided to replace the bead front sight with a post front

sight.

Brownells

sells a post front sight with a white line in the center for

$30. I decided to

try to fabricate my own using materials I had on hand.

Brownells sells a 12-inch piece of 3/8” dovetail

blank which used as the base for my new sight, and I had some

1/8-inch steel bar for the post.

I

used CorelDraw® to design the front post, then exported the

pattern to my CAD/CAM program.

I used my hobby CNC mill to cut a channel in the base

for the post, and to cut out the base from the dovetail blank.

I also used the CNC mill to cut out the post from the

1/8-inch bar stock. I

silver-soldered the post into the channel I milled in the

base, then milled a 3/64 groove in the front ramp of the post.

I bead-blasted the new sight, cold-blued it, then

applied white appliance touch-up paint to the groove.

Refer to my article Fabricating

a Custom Front Sight for details.

The

dovetail base was just slightly larger than the dovetail in

the barrel ramp. I

used my 65-degree dovetail file to file one side of the sight

base until it fit.

Ghost-Ring

Rear Sight

The fact that this rifle came with an original tang peep sight

was one of the selling features for me.

The tang peep sight had a single, target aperture that

folded forward out of the way so the peep could be used as a

ghost-ring. I find

that a ghost-ring works well for my aging eyes, and I don’t

have to worry about lining up a rear sight, front sight, and

target. My eye

doesn’t really see the large aperture ghost-ring, but my

brain does and automatically lines up the front sight into the

center of the ghost-ring, so once sighted-in, where ever the

top of the front sight is, that is where the shot will go.

However,

this sight was not windage adjustable.

When I attempted to bore-sight the rifle with a laser I

discovered I had to drift the front sight almost 1/8-inch to

the left, which meant I also had to drift the leaf sight that

much to the left as well.

This did not appeal to me and I felt it destroyed the

aesthetics of the rifle, so I decided to replace the tang peep

sight with a windage-adjustable ghost-ring.

I

found three different types of peep sights for the 39A that

were adjustable for both windage and elevation that I could

use as a ghost-ring; two were receiver mounted and one was

tang mounted. Those

three sights were:

- XS®

Sight Systems model ML00075– This is a

receiver-mounted ghost-ring that comes with a square post

front sight. Although

this sight is adjustable for both windage and elevation it

is more of a modern hunting sight and didn’t really

appeal to me.

- Williams®

Gun Sight Company Inc. models FP and 5D – These are

also receiver mounted sights adjustable for both windage

and elevation. The

5D is the less-expensive model and does not have the

locking micrometer adjustments of the FP.

To be used as a ghost-ring sight I would simply

unscrew the aperture and use the threaded hole.

- Marble

Arms® model 009827 – This is their tang peep sight

#8 and it is designed to fit the peep sight holes in the

tang of the older 39A models.

This was the most expensive of the three sights,

but was also more period-correct, and adjustable for both

windage and elevation.

I have this sight on a number of other lever rifles

I own and prefer it over other styles.

To make it a ghost-ring I unscrew the aperture and

use the threaded hole.

I

decided to replace the original 1947 peep sight with the

Marble Arms® #8 sight. The

sight base and screws fit the predrilled and tapped holes

perfectly. I was

able to adjust both windage and elevation so I didn’t have

to play with the front sight.

Refinishing

the Stock

This rifle came with a dark walnut butt stock and forearm with

an oil finish. However,

over the years the wood had acquired some nicks and felt dry

and rough to my hands. I

decided to refinish the wood to make it smoother and more

attractive. This

is not a collectable, it is a shooter, but I wanted it to look

good and function well.

I

removed the forearm by first driving out the magazine tube

band pin. I then

removed the two forearm tip screws and pulled the magazine

tube out of the rifle. The

forearm fell out in my hands.

I removed the butt stock by removing the tang screw and

pulling the butt stock off of the receiver.

One

of the goals of refinishing a gun stock is to remove as little

wood as possible. Over

the years I have ruined gun stocks by over-sanding trying to

remove old finish. The

secret is to use a good quality stripper so I don’t have to

excessively sand the wood.

I

stripped the old finish off the wood by applying BIX®

stripper that I purchased at my local home improvement store.

I applied the stripper with a brush by dabbing it on

very thick and letting it set for 15 minutes, then I scraped

off the excess stripper with a business card.

I applied a second coat of stripper and again let it

set for 15 minutes. I

again scraped off the excess stripper with a business card,

then scrubbed the wood with water and #2 steel wool as

described in the instructions.

After

stripping the wood I steamed out any dents by applying a wet

washcloth to the bare wood and ironing the wet cloth.

This also raised the grain in preparation for sanding.

Once

the wood was dry I sanded it with 400-grit sand paper.

I only wanted to remove the feathers raised from the

steaming process, not alter the shape of the wood.

I wrapped a strip of 400-grit paper around a roll of

soft leather. The

leather roll helps to maintain the shape of the wood without

leaving any dents or flat spots.

The above photo shows the difference between the

original butt stock and the stripped and sanded forearm.

I

removed the sanding dust with a tack rag (an old T-shirt

worked well) and applied a coat of Minwax®

Gunstock #231 stain. This

stain goes on brick red in color, but when the excess is wiped

off, it leaves a brownish-red color.

Over

the years I’ve tried different finishes on gunstocks.

Each has advantages and disadvantages; some are easier

to apply, whereas others are easier to repair.

My favorite is Birchwood

Casey Tru-Oil®. It

is easy to apply, gives a beautiful soft sheen luster to the

wood, it’s durable, and it’s easy to repair.

After the stain dried I applied three coats of Tru-Oil®.

I allowed each coat to dry for 12 hours, then went over

the wood with 000 steel wool.

The above photos show the refinished fore end next to

the original butt stock, but really don’t do justice to the

result.

Before

reinstalling the outer magazine tube I ran a cleaning patch

through it to make sure it was cleaned and lubricated.

Very few people ever clean the magazine tube, which can

accumulate dirt. In

fact I once had a lever-action rifle stop feeding and jam on

me because the follower got jammed in a dirty magazine tube.

Wouldn’t you know it happened in the middle of a

shooting competition!

When

I tried to reinstall the outer magazine tube I soon discovered

just how difficult this was to accomplish.

Because I had to install the forearm first which

covered the magazine tube hole in the receiver, I couldn’t

get the tube aligned in the hole.

My solution was to install the outer magazine tube

until it touched the front of the receiver, then I took a

pistol/revolver cleaning rod and inserted it into the

cartridge feed hole in the receiver.

I used the cleaning rod to align the tube; it literally

took 5 seconds to wiggle (gunsmithing technical term J)

the rod while pressing on the magazine tube until it clicked

in place.

Butt

Plate

The

butt plate had a number of chips around the holes probably

because this was not an original butt plate and the

countersinks didn’t fit the screws.

There was a large chip missing from the top of the butt

plate as you can see in the above photo.

Since this butt plate fit the stock I really didn’t

want to purchase a new one and go through all the fitting, so

I decided to try to repair it with epoxy.

First

I took a countersink bit and trimmed around the holes.

This allowed the screws to fit better.

Then I sprayed some release agent I purchased from

Brownells around the top screw and mounted the pad to a piece

of 2x4. The

release agent prevented the epoxy from sticking to the screw.

I read somewhere that Pam®

cooking spray makes a good epoxy release agent, but I’ve

never tried this. I

did not tighten the screw because I wanted to be able to

rotate the butt plate.

I

drilled two small holes in the hollow I planned to fill with

epoxy. This gave

the epoxy some additional hold.

I mixed some J-B

Weld® and added some black dye from a Brownells Acraglas®

bedding kit, then applied the epoxy to the chipped area using

a toothpick. I

made sure the holes I drilled were filled with the epoxy, and

that the epoxy was higher than the surface of the butt plate.

In the above photo notice the cleaned up countersink

around the bottom hole. While

the epoxy was curing I rotated the butt plate to prevent the

top screw from getting glued in place.

After

the epoxy cured I used 180-grit sand paper wrapped around a

file and sanded it down flush with the surface of the butt

plate. Then I

polished the surface with 400, 600, then 1000-grit wet/dry

sand papers also wrapped around a file.

The file kept the sand paper flat and gave me more

control when sanding. Finally

I used jeweler’s rouge on a felt wheel with my high speed

rotary tool running at the slowest speed to final polish the

butt plate. I took

the counter sink bit and cut away the excess epoxy from the

screw hole. As

shown in the above photo, you can see the epoxy patch, but the

shape is now nice and smooth.

I was actually very surprised how well this repair

turned out. I had

thought about applying a coat of paint, but I decided not to

because I felt the paint might flake off over time, and I

wanted to show-off my repair.

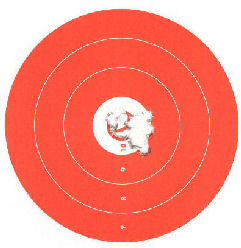

Result

The

photo above shows the result of my work.

The wood actually came out a little lighter in color

from the original, but you can see the semi-gloss finish from

the Tru-Oil®.

The

real question is, however, how does it shoot?

Well, this is one sweet rifle to shoot, and I can see

why it is so popular and still in production.

The action is smooth, the trigger is light and crisp,

and it pretty much shoots into one hole. The above

target is 15 shots at 25 yards.

Overall I’m not only pleased with my work, but I’m

very pleased with the rifle.

I’ll be shooting this one for many years.

|