The Marlin Lever Action Cycle

by Roy

Seifert

Click here to purchase a CD with this and

all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer: This

article is for entertainment only and is not to be used in lieu of a

qualified gunsmith. Please

defer all firearms work to a qualified gunsmith.

Any loads mentioned in this article are my loads for my

guns and have been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of these loads,

or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a

professional gunsmith, just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well

as a tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without the

assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this

article require special tools and cannot/should not be performed

without them.

Warning: Disassembling

and tinkering with your firearm may void the warranty.

I claim no responsibility for use

or misuse of this article. Again,

this article is for entertainment purposes only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark of

their respective manufacturers. Click on any

blue text to go to a

product/seller web site.

Introduction

Ever since getting into Cowboy Action Shooting, I

have been totally infatuated with lever-action rifles.

I have several Marlins in my collection: an

1894 CB in .45 Colt, an 1895 CB in .45-70, a 336 in .30-30, and a 39A in .22

S/L/LR. All but the 39a have the

same action. The 336 and 1895 have

an internal round bolt, and the 1894 has an external “square” bolt.

The round bolt receivers are stronger because the rear of the receiver is

closed, whereas the square bolt receivers are open in the rear to allow the bolt

to cycle.

There

have been many comments in the gun forums about how this action functions, some

of which disagreed with each other.

So, I decided to find out for myself how this action worked.

This way I could see what areas I needed to polish and be able to

troubleshoot any problem that may arise.

The

photos in this article are for my 336, but the description of the cycle applies

to most, if not all, big-bore Marlin lever-action rifles.

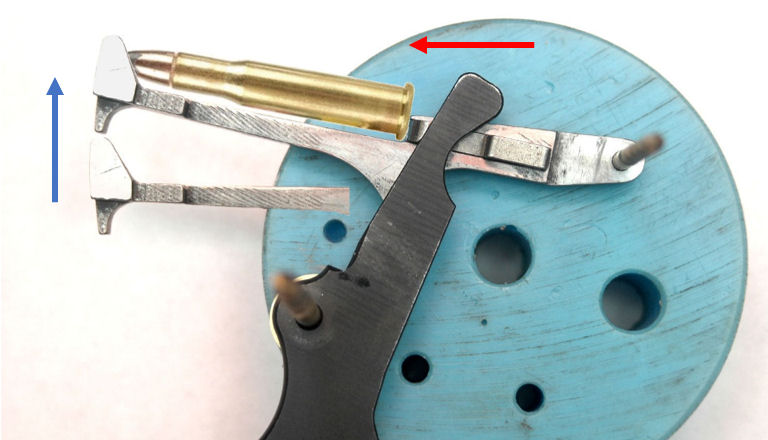

It is difficult to see how the parts interact when installed in the

rifle, so I drilled two holes the proper distance apart in a bench block to

mount the carrier and lever.

There

are two different types of levers depending on when the rifle was built.

A pre-1985 lever is flat with two large bevels on the right side.

The 1985 and later lever has a large slot milled on the right side with

two small bevels. I’ve tested both

in my 1976 336 and they both seem to function properly but using a 1985 lever in

a pre-1985 rifle should be checked and installed by a competent gunsmith.

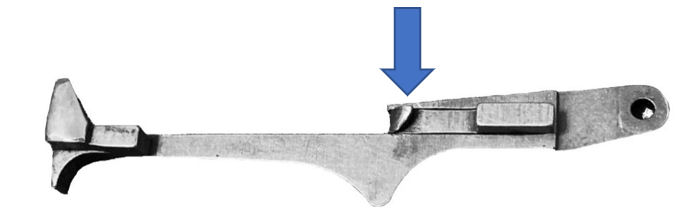

Carrier Rocker

The

carrier rocker sits in a groove milled into the carrier and rotates on a pivot

pin. There is a small spring

underneath the rocker to hold it out and against the lever.

Target Suite has an excellent YouTube video on how the lever and carrier

interact.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nWVUaa3iAcM

The

hook on the end of the rocker causes the carrier to move up so the bolt can feed

a cartridge from the carrier into the chamber.

The rocker pivots so the lever can slide over the hook when the action is

opened.

There

are two lips or ledges on the carrier; the lip on top where the rocker rides

prevents the cartridge from traveling any farther onto the carrier, and the

front edge of the lever presses against the lip on the front left to force the

carrier down at the end of the feed cycle.

The

Action Cycle

The four main parts that control the feeding of the cartridge from the magazine

tube to the chamber are the lever, carrier, bolt, and loading gate.

Yes, the loading gate serves an important function.

With

the lever closed, the front edge of the lever holds the carrier down, the bolt

is closed, the bolt lock is up and held in place, and the top of the lever and

bolt lock keep the bolt closed. The

lower bevel of the lever holds the next cartridge rim against the front notch in

the loading gate preventing it from moving further rearward, which facilitates

loading another round through the loading gate.

Without the loading gate in place there is nothing preventing a cartridge

from being pushed out of the magazine tube.

When

the lever is opened, during the first 3/4-inch of travel, the bolt lock is drawn

down from the bolt, the lever is unlocked from the bolt lock, and the cartridge

is allowed to move back onto the carrier.

If the lever is closed at this time, the bolt lock is raised to the

locked position, the hook in the lever is locked into the bolt lock, and the

cartridge is moved forward by the lower bevel on the lever so the rim of the

cartridge is again visible in the front notch of the loading gate.

This permits the magazine tube to be topped up.

As the action is opened, the lever approaches the rocker hook, the bolt

opens and moves to the rear, and the cartridge continues moving onto the carrier

pushed by the magazine spring and controlled by the front edge of the lever.

The cartridge case head rides on the front edge of the lever during the

open half of the cycle.

Towards the end of its travel, the lever rides over the rocker hook which pushes

it down against the spring. When the

lever reaches the fully open position, the spring under the rocker pushes the

rocker out so the hook at the end engages the front of the lever.

A cartridge is now completely on the carrier and is ready to be fed into

the chamber.

A

small cam on the right side of the lever strikes a lobe on the bottom of the

carrier that moves it up about 1/4-inch to block the next cartridge in the

magazine tube and prevent it from feeding.

If the carrier does not move up to block the next cartridge you can get

the dreaded “Marlin jam”, which is a double feed.

The next cartridge in the magazine tube feeds onto the carrier, but since

there is a cartridge already there, part of the second cartridge is on the

carrier, and part is still in the tube effectively preventing the carrier from

rising and jamming the rifle.

This

can be caused by either a worn cam on the lever, or a notch worn on the bottom

of the carrier by the sharp edge of the cam.

To prevent this from happening, the sharp edge of the cam should be

slightly rounded so it won’t dig a groove in the bottom of the carrier.

If the groove is already there, it can be welded up then filed down, a

hardened shim made from a hacksaw blade can be soldered over the groove or

replace the carrier. If the rifle is

used for hunting and occasional shooting, this problem may never occur.

But an 1894 model used for Cowboy Action

Shooting may see hundreds, if not thousands of rounds.

It’s best to round that edge to prevent the problem from happening.

When

the action is closed, the rear of the carrier rocker hook rides along the front

edge of the lever which causes the carrier to rise.

This aligns the cartridge with the chamber.

As the top of the lever moves forward, it pushes the bolt forward which

begins feeding the cartridge into the chamber.

The cartridge is now under control of the bolt.

The tongue at the bottom of the carrier prevents the next cartridge from

being fed from the magazine tube.

When

the carrier rocker hook reaches the bevel in the bottom of the lever, the lever

slips off and over the hook. By this

time, the cartridge has started into the chamber.

The bolt continues moving forward pushing the cartridge into the chamber.

The next cartridge in the magazine tube prevents the carrier from

falling. If this is the last

cartridge, the carrier is free to fall, but as mentioned before, the cartridge

has already started into the chamber and is under control of the bolt.

The

front of the lever contacts a lip on the front of the carrier and forces the

carrier down if it hasn’t already fallen.

The bolt moves into the closed position and the bolt lock moves up into

the locked position. When the

carrier is pushed down the next cartridge is fed from the magazine tube until it

contacts the bottom bevel on the lever which holds that cartridge in place

against the loading gate ready for the next feed cycle.

Comparing the two levers, it seems that on the 1976 model the carrier rocker

hook rides along the side of the lever until the lever gets into the fully open

position. Then, when the hook

reaches a bevel on the bottom of the lever it is pressed in so it again rides

against the side of the lever. The

bevel on top of the lever depresses the rocker during the opening cycle, and the

bevel at the bottom disengages the hook curing the closing cycle and forces the

cartridge case head against the notch in the loading gate.

The

1985 lever has a channel milled in the side.

During the opening cycle the hook rides it this channel thereby reducing

stress and wear on the hook. Again,

the top bevel depresses the rocker during the opening cycle, and the bottom

bevel disengages the hook during the closing cycle and forces the cartridge case

head against the notch in the loading gate.

The

bottom bevel controls the timing of the carrier; it determines when the rocker

hook disengages from the lever during the closing cycle.

When the hook reaches this bevel, the carrier is free to move down, but

the next cartridge in the magazine tube pressing against the front of the

carrier keeps it up until the front of the lever strikes the lip on the rocker

and forces it down. If the magazine

tube is empty, there is nothing preventing the carrier from falling.

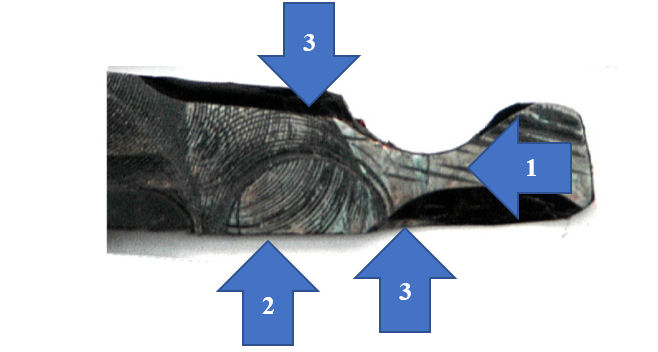

Polishing

If you

refer to my article

Building a Backpacker “Scout” Rifle you can see what areas

I already polished on my 336. Based

on what I discovered with this article I did a bit more polishing on the lever.

Before polishing I covered all the areas with a blue marker where the

cartridge and/or carrier made contact with the lever so I could see the wear

marks.

1.

I

polished the right side flat with a 220-grit stone to remove the tooling marks,

then finished with a 320-grit stone followed with 600-grit wet/dry sandpaper.

2.

I

polished the bottom edge (where the cartridge head and rocker hook ride) with a

320-grit stone, then finished with 600-grit wet/dry sandpaper.

3.

I

gently polished the bevels with a Cratex bit and my Dremel tool.

After

polishing all the surfaces, I cleaned the exposed bare metal with acetone, then

cold-blued the entire top of the lever with

Brownell’s Oxpho-Blue. I heated

the top of the lever with a heat gun, then applied the Oxpho-Blue with a large

cotton dauber. I kept the metal wet

with the dauber for 60-seconds, then wiped off the excess liquid with a paper

towel. I used 000 steel wool to card

the metal, then finished with a coat of gun oil.

I reinstalled the lever into the rifle and cycled some dummy rounds to

ensure the rifle functioned properly.

Summary

This exercise showed me exactly how the Marlin action works so I could continue

to polish those areas where metal contacted metal.

I did the same exercise for my Ruger Redhawk (refer to my article

Performing an Action

Job on a Ruger Redhawk) so I could see what areas needed polishing for

an action job.

A bench block is a

nice tool to have for this type of work.

You can find them at

MidwayUSA.com,

Brownells, and even on

Amazon. I use my bench blocks for

this type of work, and for removing pins.

I let the pins fall through the holes so I don’t lose them on the floor.

|