Restoring

a Ted Williams Model 100 .30-30

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

I really

enjoy working on a project gun.

There’s a tremendous sense of pride in turning a

junker into a fine looking and shooting firearm.

I recently purchased a saddle and built a saddle stand

for it primarily to show off my leatherwork.

I wanted a lever-action rifle to display in the

scabbard, but found the pewter replicas to be far too

expensive at $180-$225. Searching

through the used gun rack at my local gun store I found a

well-abused Ted Williams model 100 .30-30, which I purchased

for the very reasonable price of $225.

This model is really a

Winchester

94 sold by Sears under the Ted Williams name.

With a magazine plug in place and the firing pin

disabled, this would make a fine display piece in the leather

scabbard mounted on my saddle.

Initial Assessment

This is an example of a no frills, classic,

Winchester

.30-30. It does

not have an external safety other than the half-cock notch on

the hammer, nor does it have fancy sights.

It has a leaf main spring instead of the coil spring

and rebounding hammer.

As

mentioned before, this rifle looked like someone had very much

abused it. From

the amount of surface rust it was probably left in a soft gun

case/bag for an extended period.

It may also have been left in a closet, as there was

white paint on the barrel and magazine tube.

The previous owner had engraved his driver’s license

number on the bottom tang, which I will have to remove.

It

looked like the wood had been replaced and had some nicks and

scratches, but was in otherwise excellent condition.

The original Sears butt plate did not fit properly as

you can see in the above photo.

Because the end of the butt stock was wider than the

butt plate the stock was prone to chipping.

The

fore end had about 1/16 inch play forward and backward as you

can see in the above photo.

I

think the worst case of abuse I found on this rifle was the

front sight. It

looked like someone had tried to replace the front sight with

a higher one, which did not fit into the dovetail, or they may

have removed the front sight to mount a scope, then tried to

re-install it when they sold the rifle.

Most of the scope mounting hole plug screw slots were

buggered. In the

photo above you can clearly see the gap below the bottom of the

sight.

I scrubbed the bore with Remington Bore Cleaner and

fortunately, the bore looked fairly clean and sharp.

The lands were nice and sharp at the muzzle, indicating

to me that the rifle was not used much, nor cleaned very

often. There was,

however, some surface rust in the bore.

Restoration

Plan

This rifle is not really going to be a shooter, although it

could be. It’s

mostly for display purposes so I plan to reassemble it so it

cannot be fired. However,

since I have it apart I’ll do some basic work to it if I

ever want it to be a shooter.

-

Remove

the front and rear sights.

-

Completely

disassemble the rifle and check for internal rust/damage.

-

Unscrew

the barrel from the receiver.

-

Remove

the surface rust from the barrel and lever.

-

Remove

DL number, polish and refinish lower tang.

-

Refinish

receiver.

-

Lap

the bore.

-

Clean

up the muzzle crown.

-

Lap

the barrel shoulder to the receiver.

-

Modify

bolt for smoother action.

-

Perform

a trigger job.

-

Reassemble

the rifle with dry-firing firing pin.

-

Glass

bed the fore end to remove looseness and refinish.

-

Replace

and install the sights.

-

Fill

chips in butt stock.

-

Replace

and fit new butt plate.

-

Refinish

butt stock.

-

Add

a saddle ring.

-

Inlet

a Morgan silver dollar into the butt stock.

Remove

Sights

Removing the sights was easy; they tapped right out from left

to right with a brass punch.

The front dovetail on the front sight was peened up

because the sight was installed incorrectly, so I took a punch

and flattened as much of the raised lip as I could.

Completely

Disassemble the Rifle

I completely disassembled the rifle and found no rust inside.

This was good news!

Some screw-heads were buggered from someone using

hardware store tapered screwdrivers, or incorrect sizes of

screwdrivers, but I cleaned those up with a file and

cold-blued.

Unscrew

the Barrel from the Receiver

I used my Action Wrench with a universal head, and my barrel

vise to unscrew the barrel from the receiver.

I put tape around the front of the receiver before

installing the action wrench.

Separating the barrel and receiver will make them

easier to work on.

Remove

the Surface Rust from the Barrel and Lever

This rifle did not really have any deep rust pits, so it was

easy to remove the surface rust with 000 steel wool and gun

oil. I put a few

drops of Hoppes gun oil on a piece of 000 steel wool and

worked it over the metal.

The surface rust came right off but left a slight

blemish. With a coat

of good gun oil you can hardly see these blemishes.

After rubbing with the oiled steel wool I wiped off the

part with a clean rag, sprayed with brake parts cleaner to

remove any old oil and grease, then coated with Breakfree CLP.

The photos above show the results.

Remove

DL Number, Polish and Refinish Lower Tang

That driver’s license number was unsightly on the lower

tang. First I

removed all parts from the tang, then, using a bastard file, I draw-filed just enough to remove

the DL number. Using

a shoeshine motion, I then polished the surface with 320-grit

wet/dry paper until there were no file marks.

I taped the edges of

the tang to protect the bluing then bead-blasted the newly

polished surface. I

cleaned the blasted surface with acetone, then cold blued.

The result is shown in the above photo.

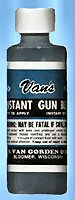

A note

about cold bluing: I

use Van’s Instant Gun Blue because I like the results.

The part I’m bluing must be perfectly clean; I use

acetone for cleaning. For

small parts, I like to immerse them in the gun blue solution.

I use small aluminum tins I purchased at the grocery

store. For

large parts, I use a toothbrush to brush the liquid on the

part, constantly keeping the part wet so the bluing can work.

This is not a “wipe and go” product.

I let the part soak/stay wet for 3 to 5 minutes, wipe

it dry, then coat with a good gun oil.

Refinish

Receiver

This receiver could not be rescued with just steel wool and

oil. I

bead-blasted the entire receiver until all rust and old bluing

was removed. I

thoroughly cleaned it with brake parts cleaner and acetone,

then immersed it in the cold bluing solution for about 5

minutes. I removed

it from the solution and wiped it clean, then sprayed it with

Breakfree CLP and let it set for a while.

I removed the excess CLP and the photo above

shows the result, with which I was quite pleased.

Cold blue is not as durable as hot bluing, but I think

this will be good enough for my purposes, as long as I keep it

oiled.

Lap

the Bore

Since I had the barrel off I decided to lap the bore.

The bore did have some rough spots and maybe some

pitting, so I decided to see if I could smooth it out a bit.

I may eventually fire-lap it, but for now I’m going

to hand lap. I put

a .22 bronze cleaning brush on a rifle cleaning rod and put

masking tape on the end of the rod.

I put just enough tape to make a snug fit in the bore.

The tape prevents molten lead from running down the

bore. I inserted

the brush into the barrel from the chamber end until it came

about one inch from the muzzle.

I poured molten pure lead (NOT lead alloy) down the

bore from the muzzle end until the lead came almost to the end

of the barrel.

I pulled

the lead lap back through the bore until I could unscrew the

cleaning rod. I

attached another cleaning rod, this one without tape, and

pushed the lap through the bore until it protruded about two

and one half inches beyond the muzzle.

I coated the lap with 400-grit lapping compound and

worked it back and forth through the full length of the

barrel. I reloaded

the lapping compound twice before having to make another lap.

I loaded that lap 3 times with lapping compound before

calling it quits.

I sprayed

brake parts cleaner down the bore and around the muzzle, then

swabbed out the bore to thoroughly remove all traces of grit

and lapping compound. I

then ran an oily patch down the bore to protect it.

After I was done the bore was shinier, but I could

still see some rough spots.

I will definitely have to fire-lap it to get it really

smooth.

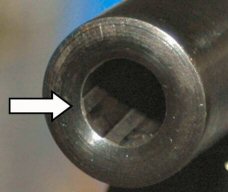

Clean

Up the Muzzle Crown

I always perform this procedure when I acquire a new gun.

I purchased brass muzzle laps from Brownells

and selected the appropriate size

for .30 caliber. I

put the lap in my hand drill and dipped the end in 400-grit

lapping compound. With

the drill on slow speed I put the end of the lap against the

muzzle and used a rotary motion with my wrist to prevent the

lap from wearing unevenly.

Notice the angle of the lap in the photo.

After about 30 seconds I cleaned the muzzle with brake parts

cleaner and oiled. This

made the ends of the lands and grooves nice and sharp as you

can see in the above photo.

Lap

the Barrel Shoulder to the Receiver

For most modern firearms the barrel is usually screwed much

too tightly to the receiver.

This can cause undue stress in both the barrel and

receiver, which can have an adverse affect on accuracy.

Before unscrewing the barrel, I took a prick punch and

made a witness mark between the bottom of the barrel and

receiver. This is

so I would properly align the barrel when I put it back

together. With the

barrel just touching the receiver, the two witness marks were

about one quarter inch apart.

I put 400-grit lapping compound between the shoulder of

the barrel and the receiver and alternately tightened and

loosened the barrel until the witness marks were about one

eighth inch apart. I

was careful not to get any compound on the barrel threads or

the barrel would be too loose.

I cleaned all the compound from the barrel and receiver

with brake parts cleaner and acetone.

When it came time to reassemble the barrel and

receiver, I put Loctite 222 on the barrel threads and Loctite

609 on the barrel shoulder.

Using my barrel vice and action wrench I tightened the

barrel until the witness marks were aligned.

Modify

Bolt for Smoother Action

The action on this rifle was very stiff.

Actually, it’s no different than any other

Winchester

94 I’ve handled. I

sometimes could not even open the action with the rifle

mounted on my shoulder. After

examining all of the moving parts, I determined that the

mainspring and the hammer rubbing along the bottom of the bolt

caused most of the stiffness.

I completely backed out the hammer tension screw

thereby setting the mainspring (a leaf spring) to its lowest

setting.

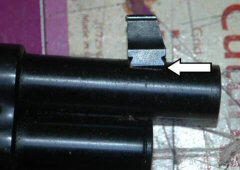

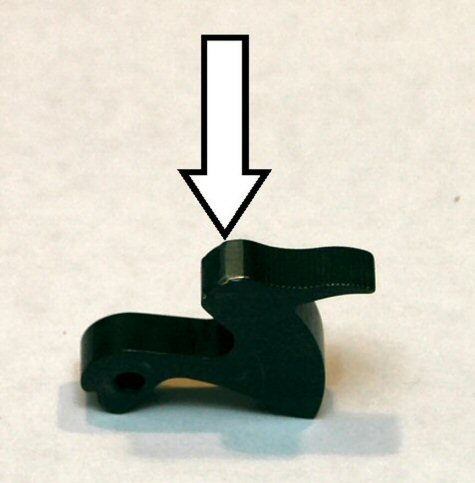

In

the photos above you can see where the hammer rides

along the bottom surface of the bolt.

The arrow points to the camming surface that cocks the

hammer. The arrow

in the right photo shows the corresponding surface on the

hammer that rides along the bottom of the bolt.

I wanted to reduce the amount

of surface area rubbing against the hammer by milling the

edges of the camming surface leaving only about one eighth of

an inch in the middle as shown by the red box in the left photo.

This would reduce friction making the action lighter.

First I took my Dremel tool with a Cratex wheel and

polished the bearing surface of the hammer, then refinished it

with cold blue.

I put the bolt in the machinist vise on my mill and used a

one-quarter inch square end bit to mill each side of the bolt

bottom even with the rear of the cam as shown in the two

photos above. The bottom photo

shows the depth to which I milled the bolt.

I then polished the entire cam surface and cold blued.

This reduced the amount of bearing surface, which

significantly lightened the action.

I can now easily work the action from my shoulder.

Perform

a Trigger Job

The trigger on this rifle was long and creepy and broke at 8

pounds. I decided

I wanted a lighter, crisper trigger so I performed a trigger

job. Please note

that these procedures should not be performed without

the appropriate tools! Trigger

weight was determined by a number of factors:

I

decided not to change the mainspring or sear spring tensions,

primarily because they are both leaf springs that are more

difficult to adjust. The

hammer engagement surface was already 0.014” deep so I

decided to leave that alone also.

The

sear looked like it was only engaging about 1/3 of the

hammer-mating surface. First

I put the sear in my Power Custom Series 1 stoning fixture

with the Ruger MKII adapter and rotated the adapter until the

sear surface was parallel to the ground as seen in the above photo. I then

adjusted the fixture so a coarse ceramic stick was perfectly

flat against the sear surface.

I did this by marking the engagement surface with blue

marker and taking a couple of strokes with the ceramic stick.

I adjusted the jig until the blue was removed evenly

across the surface. I

then polished the entire engagement surface first with a

coarse ceramic stick, then with a fine ceramic stick.

I then rotated the adapter so the rear edge of the sear was

up, and stroked that edge about 15-20 times with the coarse

ceramic stick. This

put a breakaway angle on the sear.

This method reduces the amount of sear that engages the

hammer without having to remove any metal from the hammer.

Finally, I cut an angle on the left edge of the sear so

only about 2/3 of the sear was engaging the hammer as

illustrated in the above photo.

I

reassembled and lubricated the action, and found that the

trigger now broke cleanly at exactly 4 pounds with no creep.

This is great for a shooter.

Reassemble

the Rifle With Dry-Firing Firing Pin

I completely reassembled the rifle to check for function.

I noticed that the cartridge guides were originally

installed with some type of lacquer to prevent them from

coming loose. I

used Loctite 609 when I installed them by first cleaning the

guides and their corresponding channels in the receiver with

acetone, then applying the 609 to the back of the guide.

Loctite 609 is specifically designed to be used where

metal touches metal as in this application.

The locking

bolt has a chamfer around the firing pin striker.

When the rifle is dry-fired and the hammer strikes this

chamfer it peens the corners of the hammer, which raises burrs

and leaves unsightly marks on the hammer.

I wanted to be able to lever and dry-fire the rifle,

but did not want to use Snap Caps because they would be

ejected. I also

did not want the rifle to fire a cartridge.

I

took four coils from a 0.197” diameter spring made of

0.033” wire from my Brownells spring kit #71 and placed it

on the front of the firing pin as shown in the photo above.

When I reassembled the rifle I had to press in on the

firing pin to get the locking bolt in place.

The lever pivot pin held the firing pin in place, and

the spring allowed me to dry-fire the rifle without actually

firing a primer. I

inserted a 16-inch long, 1/4-inch dowel in the magazine tube.

This way the rifle can’t be loaded from the magazine

tube, nor fired.

Glass

Bed the Fore End to Remove Looseness

As mentioned before, the fore end was loose so I decided to

bed it to the frame. I

added enough bedding compound at the rear of the fore end to

make it fit tightly against the receiver.

I drilled a few holes in the rear surface of the fore

end to help give the epoxy more gripping surface.

I taped the outside edges of the fore end and receiver

and put some clay plugs at the top of the fore end to act as a

dam. I then

sprayed the receiver, barrel and magazine tube, and outside of

the fore end with release agent.

I

put the rifle back together being careful not to get any

release agent on the rear face of the fore end.

I mixed my bedding compound that I purchased from Brownells

and poured it into the gap.

I kept turning the rifle over and wiping away the

excess. I added

more compound to the gap as needed.

In the photo above you can see the clay I used to make a

dam to prevent excess compound from running out.

Even so, you can see some epoxy did spill over.

After the epoxy hardened to the consistency of plastic I

removed the clay, tape, and the fore end.

A large quantity of epoxy had run into the magazine

tube channel, which I had to remove with a sharp knife.

I also had to cut away excess epoxy from other places

around the fore end. This

was an easy task thanks to coating the areas with release

agent. I then let

the epoxy set for 24 hours.

The photo

above shows the result. The

tiny hole in the upper right corner is one of my drilled holes

that did not get filled with epoxy.

Once the

epoxy cured, I removed the old oil finish with oven cleaner

and commercial finish remover.

I sanded it lightly with 320-grit, then 600-grit sand

paper. I steamed

up the grain and dents by putting a wet cotton T-shirt over

the wood then running a hot iron over the wet shirt.

I did this three times, and lightly sanded with

600-grit sandpaper after each time.

Finally, I coated the wood with three coats of

Birchwood Casey Tru-Oil. You

can see the result in the above photos.

Replace

and Install New Sights

I purchased a Marbles 45W 1/16 gold bead front, and a Marbles

#67 long semi-buckhorn rear from Midway USA to replace the

buggered-up sights. These

sights were just a bit

wider than the dovetail slots

in the barrel so I took my 60-degree dovetail file and started

to remove metal from one side of the sight a little at a time.

I took off just enough metal so I could start the sight

by hand on the left side of the rifle.

I then took my homemade sight punch and tapped the

sight in place. I

do not like to use steel or brass punches to drift sights

because brass leaves marks, and steel can mar the sight.

I take a steel punch and wrap thin leather around the

front to protect the sight as shown in the top photo.

The bottom photo shows the new sight installed.

Fill

Chips in Butt Stock.

I took some leftover epoxy from bedding the fore end and

filled the chips in the butt stock as you can see in the above

photo. When the epoxy

was hard enough I cut along the edge and removed the butt

plate to allow the epoxy to fully cure.

I sanded the epoxy ball in the process of fitting the

new butt plate.

Replace

and Fit New Butt Plate

As with most of the rest of this rifle, the original Sears

butt plate had pits, dings, dents, and scars and was very

unsightly, which you can see in the photo above.

I purchased a

Winchester

butt plate model W52 from Vintage

Gun Grips. This

butt plate fit the stock much better than the old Sears butt

plate, but the original screw holes did not line up.

I

drilled out the old screw holes with a 1/4-inch drill bit,

then glued in a piece of 1/4-inch hardwood dowel. I

carefully measured where to mount the new butt plate, marked,

and drilled the new holes.

I then mounted the butt plate to the butt stock.

I used my belt sander mounted in a vise to carefully

sand the edges even with the butt stock.

I sanded the edges with 600-grit sand paper, then

finished them with fine polishing grit and a felt Dremel pad.

Refinish Butt

Stock.

I removed the old finish with oven cleaner and a commercial

stripper. I

completely sanded the stock, then steamed out the dents and

raised the grain three times, as I did with the fore end.

Walnut has many gaps in the grain so after raising the

grain the third time, I went over the entire stock with a

walnut-colored wood filler and sanded with 320-grit sandpaper.

I went over the entire butt stock with 600-grit sand

paper to ensure it was nice and smooth. I

finished the butt stock with three coats of Tru-Oil, lightly

buffing with 000 steel wool between each coat.

Add

a Saddle Ring

I

have always like the looks of a saddle ring on a lever-action

rifle, so I decided to add one.

I found a photo on the internet that clearly shows the

location of the saddle ring hole in relation to the hammer and

carrier screws. In

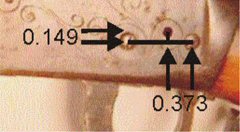

Figure 31 above, the carrier screw is on the left, and the

hammer screw is on the right.

The distance between these two screws, measured on my

rifle with calipers, was 0.96 inches.

I imported the photo into Corel Draw and sized it until

the screws on the photo were 0.96 inches apart.

I drew a line from the center of the saddle ring hole

to the line between the two screws, which measured 0.149

inches. I then

drew a horizontal line from that vertical line to the center

of the hammer screw, which measured 0.373 inches.

I

carefully measured on my receiver and made a mark with a

center punch as shown in Figure 32.

I protected the receiver with tape and put it in my

machinists vise in my mill/drill.

The saddle ring I purchased had a 10-32 stud, so I

drilled the hole using a #21 drill bit.

After

I drilled the hole, I removed the drill bit and inserted the

10-32 tap.

I left the chuck loose so the tap would spin freely and

used vise-grips to turn the tap as shown in the above photo.

This method ensures that the tap starts straight.

I removed the receiver from the vise and finished

tapping the hole with a tap handle.

In

the photo above you can clearly see the new hole.

It is in a thick part of the receiver away from any

moving parts. However,

the drilling and tapping process raised a burr.

I took a flat jeweler’s file and filed the burr

flush. There was

also a raised burr on the outside of the receiver, which I

removed with a 3/8 round end mill bit.

I turned the bit by hand until the burr was removed and

a slight chamfer was left. This chamfer was going to be

covered by the stud so it didn't matter that it was there.

I

cleaned out the newly tapped hole and the receiver with brake

parts cleaner, then coated with Breakfree CLP.

The saddle ring stud must have had a tapered thread

because it got harder to turn as the shoulder of the stud got

closer to the receiver.

I had to use a hardwood dowel through the ring to get

the stud seated.

Inlet

a Morgan Silver Dollar into the Butt Stock

When I started cowboy shooting I selected a gambler as my

character. I

wanted a money theme for my character, so I decorated my

leather with Morgan silver dollars from the 1880 decade, and I

selected “Eight Bits” (as in a dollar) for my alias.

I wanted to carry this theme into my rifle so I decided

to inlet a Morgan silver dollar into the butt stock.

I

went to my local flea market and found a beautiful, sharp,

1882-O Morgan silver dollar for $15.00.

It measured 1.488-inches in diameter by 0.11-inches

thick. In the

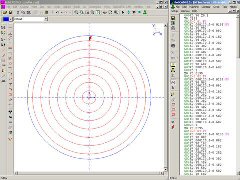

photo below you can see the CAD design for the inlet

hole. The blue

line is the actual 1.489 hole, one-thousandth over the size of

the coin. The red

line is the tool path for a 1/8” bit that will cut

0.11-inches deep. On

the right are the tool commands

for my hobby CNC mill.

I removed the butt stock from

the rifle and clamped it onto the mill table.

I put foam between the stock, the table, and the clamps

so I did not damage the finish.

I adjusted the mill and ran the program, which you can

see in photo above. While

the program was running, I polished the dollar then coated it

with a clear lacquer so it would not tarnish.

I discovered that the hole being 1.489-inches was too

narrow so I had to open it up a couple of thousandths to get

the dollar

to fit.

After the milling was

completed, I took some 600-grit sandpaper to gently sand off

the feathers of wood that were left around the edge of the

hole. I then

coated the inside with Tru-Oil to protect it from moisture.

I put a few drops of epoxy to hold the dollar in place

and pressed it into the hole.

The result is shown in the above photo.

Here

is how the rifle looks in the scabbard. Ok, so far I am

very pleased with the result.

The action is fairly smooth for a ’94, the wood and

metal look very nice, and I tested the function with some

.30-30 dummy rounds and it works perfectly.

My shooting buddy, Dave,

purchased a used Winchester 94 .30-30 that came with a

side-mounted scope for the great price of only $130.00 (can

you say great deal!) and I could not help but compare them.

Obviously, mine was the cheaper of the two.

His action was as smooth as mine was with no

modifications, and his trigger broke at 4 pounds with just a

hint of creep. A

little polishing of the sear would take care of this.

We took our rifles to the

range to try them out. I

had some 150-grain Remington® Express® Core-Lokt® and he

was shooting the same but with 170-grain bullets.

I could not get my rifle to sight-in at 100 yards using

the 150-grain bullets, but I was able to sight-in with the

170-grain. Once

sighted-in with the 170s it seemed the 150s were shooting 30

inches high. I

tried to justify that with my ballistic software, but could

not get it to work. So,

if I decide to use factory, or reload, I’ll be using

170-grain bullets.

The rifle functioned

perfectly with no misfires or failures to eject.

If I decide to use this rifle, it is definitely a

shooter. Dave was

able to use my rifle and put two shots next to each other at

100 yards using just the open sights.

I probably will not go to the trouble to fire-lap the

barrel since the accuracy is very acceptable for an

iron-sighted gun.

The bottom line here is that

I am proud of my restoration work, and the rifle functions

perfectly.

Addendum

4/8/2012

I recently

installed a Marbles tang peep sight to this rifle because I

find the peep sights easier to use with my old eyes, and

faster to acquire a sight picture.

170-grain bullets were now shooting about 18-inches

high at 100 yards with the peep sight at the lowest setting.

This meant I would have to install a taller front

sight.

I

calculated how much taller the front sight had to be and used

my hobby CNC mill to fabricate a front sight similar to the

one I made for my Marlin 39A as detailed in my article Fabricating

a Custom Front Sight.

The white line really shows up.

While

cleaning the rifle after sighting it in I discovered I had

some copper fouling. This

is normally caused by a rough bore stripping copper from the

bullet jacket. This

copper is exposed to the expanding hot gas which turns the

copper into plasma and deposits it in the bore causing copper

fouling.

I decided I

wanted to polish the bore by fire-lapping, but didn’t want

to use the aggressive method of impregnating a bullet with

lapping compound. Traditional

fire-lapping drives bullets impregnated with lapping compound

through the bore at very low velocities.

Cases used for fire-lapping have to be thrown away

because the brass case neck gets contaminated with the lapping

media. Although

this method does wonders for the bore, it also lengthens the

barrel throat which can reduce barrel life.

My method polishes the throat without increasing its

length, laps the bore and I don’t have to throw away the

cases!

First I

loaded 15 rounds of .30-30 with 5.0 grains of Red Dot behind a

150 grain FMJ boat tail .308 bullet and a large rifle magnum

primer. I used

magnum primers because there is so little powder in the case,

and anything less than 5.0 grains of powder will cause the

bullet to get stuck in the bore.

I used spire-pointed bullets because I had a bulk

supply of them, and wasn’t going to load them in the tubular

magazine.

I put a

fired case in the chamber to prevent the lap from depositing

compound in the chamber. I

wrapped a .45 cleaning patch around a 25-caliber bore brush,

and then impregnated the patch with USP

Bore Paste™ that

I purchased from Midway

USA #

257358. I ran

the tight-fitting patch back and forth through the entire

length of the bore 20 times being careful not to allow the lap

to come all the way out of the muzzle, or all the way into the

chamber. This

performed the hand lapping part of the process and left a

small amount of compound in the bore.

For this first hand lapping the patch felt tight for

all 20 passes. This

indicated a rough bore.

I removed

the empty case from the chamber and fired one low-velocity

round through the barrel which performed the fire-lapping.

I inserted the empty case into the chamber, then again

using USP Bore Paste™ ran an impregnated tightly fitting

patch back and forth through the bore 20 times.

This cleaned any powder residue and fouling from the

bore and prepared it for a second low-velocity lapping shot.

This time, after only 2 back and forth passes the patch

felt much smoother and required less pressure to push and pull

it through the bore indicating the bore is becoming much

smoother.

After

performing the lap/shoot process for 5 shots, I thoroughly

cleaned the barrel using solvent and dry patches.

This removed any residual lapping compound in

preparation for the next finer compound.

The photo

above shows a recovered lapping bullet.

You can see the dark areas caused by lapping the lands

and grooves in the bore.

I threw

away the first empty case and inserted a clean, empty case

into the chamber. Now

I impregnated a clean patch with J-B® Bore Bright #083-065-100

that I purchased from Brownells which has a finer grit and

performed the hand lap/fire lap sequence another five times as

before, then thoroughly cleaned the bore again with solvent

and patches.

Finally, I

performed the same hand lap/fire lap process another five

times using ISSO bore cleaner

#073-000-002

that I also purchased from Brownells which has the finest

grit. This process

performed the final polish of the chamber throat and bore.

The bore was mirror bright and smooth and was now ready

for full pressure loads. This

should eliminate most, if not all, copper fouling and make the

bore easier to clean.

|