Modifying

a Winchester 97 for Competition

by Roy Seifert

Click here to purchase a

CD with this and all Kitchen Table Gunsmith Articles.

Disclaimer:

This article is for entertainment only and is not to

be used in lieu of a qualified gunsmith.

Please defer all firearms work to a qualified

gunsmith. Any loads

mentioned in this article are my loads for my guns and have

been carefully worked up using established guidelines and

special tools. The

author assumes no responsibility or liability for use of

these loads, or use or misuse of this article.

Please note that I am not a professional gunsmith,

just a shooting enthusiast and hobbyist, as well as a

tinkerer. This

article explains work that I performed to my guns without

the assistance of a qualified gunsmith.

Some procedures described in this article require

special tools and cannot/should not be performed without

them.

Warning:

Disassembling and tinkering with your firearm may

void the warranty. I

claim no responsibility for use or misuse of this article.

Again, this article is for entertainment purposes

only!

Tools

and firearms are the trademark/service mark or registered trademark

of their respective manufacturers.

Introduction

The Winchester Model 1897 (or just Winchester 97) was designed

by John Moses Browning, one of the most famous American

firearms inventors. The

Winchester 97 was first listed for sale by

Winchester

in 1897 as a 12 gauge solid frame model. The

12 gauge takedown was offered in 1898, and the 16 gauge

takedown in 1900. The

97 was produced as an improved, stronger version of the

Winchester

1893 and was designed for use with smokeless powder shells.

Many

cowboy action shooters use a Winchester 97 pump-action shotgun

or similar replica for their main match gun.

I never got the hang of loading one shell and cycling

the action. Some

shooters practice until they get really fast, but after trying

and fumbling, I went back to a double-barrel.

Grab two shells, load two shells, middle finger on the

rear trigger, first finger on the front trigger, bang, bang,

open, jerk out the empties, and I’m ready to go again.

However, now that I own one I may just use it for

cowboy matches.

Often

times, however, my club has a Wild Bunch side match based on

Sam Peckinpah’s movie The

Wild Bunch. In

that movie you see the characters use such iconic guns as the

Colt 1911 .45 ACP, Winchester 97 pump shotgun, and Strother

Martin uses a

Springfield

1903 .30-06. Wild

Bunch side matches require the use of a

Winchester

model 97 or model 12 shotgun, a 1911 .45, and a pistol-caliber

lever-action rifle. I

own two .1911 45s, and a Marlin 1894 in .45 LC, but I didn’t

have the shotgun.

I found a

vintage Winchester 97 on Gunbroker.com

for $280.00; what a steal! By

the time I paid shipping and transfer the price came to

$332.00, still a great deal.

Since cowboy action shooting is becoming so popular,

and the

U.S.

no longer allows Chinese imports of firearms, these old

Winchesters just keep climbing in price.

The serial number indicated that it was manufactured in

1907 so I am now the proud owner of a 100 year old gun.

However, this gun is a shooter, not a wall-hanger.

This

shotgun came in 12-gauge with a 28” full-choke barrel, and

was the takedown model. There

is something about a takedown gun that has always appealed to

me. It also had a

cracked stock as you can see in the above photo, which was

fully disclosed by the seller.

I

thoroughly inspected the gun and found the butt stock was also

cracked on the other side in the same place.

Also, a large piece had feathered off the left side and

was re-glued in place.

Improvement

Plan

Once the shotgun arrived I disassembled it and gave it a

thorough inspection and cleaning.

I wanted to avoid buying additional parts; otherwise

this gun wouldn’t be such a great deal!

I wanted to perform the following:

- Repair

the cracked stock

- Cut

the barrel to 18 1/2” – 18” is the minimum legal

barrel length for a shotgun.

This is not a collectable gun, for me it’s a

shooter and I want to be able to use it for both cowboy

and wild bunch matches.

- Ream

and tap the barrel for internal choke tubes

- Install

a flush improved cylinder choke tube

- Install

a new bead behind the end of the choke tube

- Cut

down the butt stock to adjust length of pull – the

length of pull was way too long for me

- Install

a recoil pad to the butt stock

- Install

an Evil Roy magazine 6-round conversion kit

Rust!

One area

that is often ignored and not well taken care of by firearms

owners is the magazine tube, and this shotgun was no

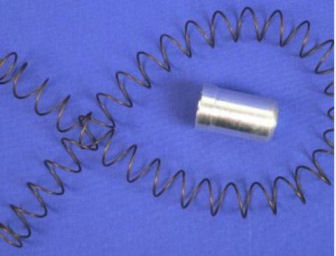

exception. Due to

years of neglect and lack of cleaning, the inside of the

magazine tube had rusted and caused the magazine spring to

also rust and break in two places.

The inside of the tube was pitted, but luckily it had

not rusted through. Case

in point here, if you have rifles or shotguns with magazine

tubes, take a few minutes to remove the plug, magazine spring

and follower and run an oiled cleaning patch through it.

This will save problems sometime down the road.

I have a Marlin 1895 Cowboy in .45 LC that the magazine

tube got so dirty the follower jammed during a cowboy match!

I now clean the magazine tube as part of my normal

cleaning routine after every match.

I unscrewed

the action slide sleeve screw cap and removed the action slide

from the magazine tube. To

remove all of the rust I used electrolysis (refer to my

article Rust Removal via

Electrolysis). I

made up five gallons of electrolysis solution mixing 1

tablespoon of Arm and Hammer Washing Soda (not baking soda) to

each gallon of regular tap water.

I took a

steel rod (not stainless steel; stainless steel produces

harmful byproducts) and placed a rubber cork at either end and

inserted it into the magazine tube.

This steel rod is the anode which I connected to the

positive (+) side of my battery charger.

The negative (-) battery charger lead I connected to

the magazine tube making sure I had a good electrical contact.

I immersed the tube into the solution, connected the

battery charger leads as explained above, and plugged in the

charger. I

immediately began to see bubbles appear, which were caused by

the water breaking down into oxygen and hydrogen.

I left the tube in the solution with the battery

charger connected for 3 hours.

I unplugged the charger, removed the tube from the

solution, and thoroughly dried it in preparation for cold

bluing.

Once the

tube was dry I immersed it into Shooter Solutions™ Rugged

Gun Blue which has become my favorite cold bluing solution

(refer to my article Shooter

Solutions™ Rugged Gun Blue).

This put a protective layer of bluing on the exposed

metal. I washed

the tube in running water to remove any traces of cold blue

solution, then thoroughly oiled the tube.

I reassembled the action slide onto the magazine tube

and made sure everything was smooth and well lubricated.

I ordered a

replacement magazine tube spring and follower from Numrich

for a total of $11.00 plus shipping.

Even though I plan to install the Evil Roy 6-round

conversion I wanted to have the original parts on hand.

Disassembly,

Cleaning, and Lubricating

I completely disassembled the gun and found a few spots of

rust inside, but the internals were in good shape.

However, they were very dry and dusty.

I cleaned all parts with solvent (Ed’s

Red) and a nylon bristle brush, sprayed them with brake

parts cleaner to remove all traces of solvent, then oiled them

with Break-Free®

CLP. I put

Brownells Action Lube Plus® #083-050-002

on the bolt rails and the action slide groove in the carrier

and reassembled everything.

Before disassembly the action was stiff, especially

when moving the action slide forward.

Now everything was light and smooth with no hitches or

binding anywhere in the action cycle.

Repairing

Butt Stock

The butt stock was cracked on both sides of the wrist so I

decided to try my hand at repairing the butt stock.

I took a tapered wooden plug and forced it into the

round opening at the front of the wrist to open the cracks

just a little; about the thickness of a business card.

I mixed some JB Weld epoxy and forced it into the

cracks with the edge of a business card.

I removed the plug and clamped the wrist to hold it

tightly closed. As

the epoxy was forced out of the crack I wiped off the excess.

Since the

stock was cracked in two places I wanted to install two

reinforcing pins to keep the crack from spreading.

I threaded a piece of 1/16” brass rod with a 4-32

tap. I drilled a

hole with a #44 drill bit from the top of the wrist through

each crack.

I cut

enough threaded rod so it would fit into the hole I drilled,

and into the chuck of my drill.

I coated the threads with epoxy and used the slow speed

of my drill to screw the pin into the hole.

I removed the pin from the chuck and cut it flush with

the stock. I filed

the end of the pin so it was flush with the stock.

Many

military surplus stocks are pinned in this manner.

I could have cut each pin short, cut a notch in the

end, screwed it below the surface of the stock, then filled

the hole with epoxy and wood dust to completely cover it up,

but I like the fact that the pins are visible.

All of my shooting friends tell me this gives the gun

character, and I got to keep the 100-year old stock.

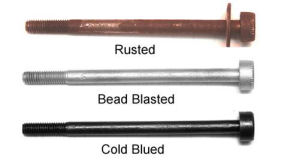

Re-Bluing

the Butt Stock Screw

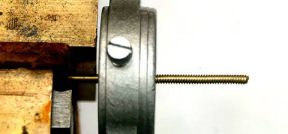

The butt

stock screw and washer were heavily encrusted with rust.

When I removed them to remove the butt stock the screw

was loose, which is probably why the butt stock cracked.

This screw had probably never been removed and became

loose over time. I

bead blasted the screw and washer with glass bead media which

removed all the rust and put a matt finish on the parts.

Because rust is corrosive you can see how pitted the

screw was after the rust was removed.

I dipped the screw and washer in Shooter Solutions™

Rugged Gun Blue, washed off the excess solution, then coated

it with Hoppes® gun oil.

The photo above shows the process and the results.

Reaming

and Threading the Barrel for Internal Choke Tubes

My long-time shooting buddy, Jon (a.k.a. “Lone Star”) also

purchased an original Winchester 97 12-gauge shotgun with a

32-inch full-choke barrel for a very reasonable price at a

local gun show. The

price was reasonable because the barrel was dented.

He wanted to make the same modifications to his gun

that I wanted to make to mine so he came over to use my shop

and my tools. He

also wanted to cut the barrel down to 18 1/2“ and ream and

thread it for internal choke tubes.

The rules of Cowboy Action Shooting™ allow shotguns

with interchangeable choke tubes so long as they do not

protrude beyond the end of the barrel, i.e. internal choke

tubes only. I

already had the tooling from adding internal choke tubes to my

Winchester

1300 Defender (refer to my article “Threading

a Shotgun Barrel for Choke Tubes”).

The process described below was for Jon’s gun, but I

did the same thing to mine.

We removed

the barrel from the receiver and removed the magazine tube

from the barrel. We

marked the barrel at 18 1/2“ plus 1/16”, then placed some

blue painters tape and a hose clamp at that point.

The hose clamp acted as a guide so the cut would be

fairly straight. The

cut was just a bit at an angle because the hacksaw blade

actually cut into the hose clamp.

Not a problem because the barrel reamer squares the

muzzle face anyway.

Next we

reamed and threaded the barrel to accept Win-Choke type of

internal choke tubes. According

to the instructions that came with the tools, the barrel

needed to be at least 0.845” diameter and ours measured

0.849”.

The barrel

bushing was too large to fit into the barrel but I don’t

have a lathe to turn it down.

Instead I installed the bushing onto a 1911 barrel

bushing mandrel that I purchased from MidwayUSA #749359

and used my mill/drill and a bastard file to turn it down

until it just fit into the barrel.

As the bushing was turning I coated it with a blue

marker to help keep the file straight and turn it down evenly.

After 3 or 4 passes with the file we tested the bushing

for fit in the cutoff portion of the barrel.

We continued to file and fit until the bushing fit

snugly into the barrel.

Reaming

the Barrel

Threading a shotgun barrel to accept internal choke tubes is a

two-step process. First

we had to ream the barrel so it had the proper internal

profile to accept the choke tubes.

A professional gunsmith would use a lathe to perform

the barrel reaming, but again, I don’t have a lathe so we

reamed the barrel by hand.

We installed the barrel vertically in a padded vise,

installed the barrel bushing onto the reamer, lubricated the

reamer and bushing with cutting oil, and inserted it into the

barrel. Using a

large tap wrench to ensure we applied equal pressure we began

the long process of reaming the barrel by turning the cutter

clockwise.

We both

became tired pretty quickly and developed blisters on our

hands. We realized

we would be here a long time so I devised a method of applying

pressure to the reamer with minimum exertion on our part.

I placed a

4” x 4” steel plate on top of the tap wrench, and then set

three boxes of bullets on top of the steel plate.

There was probably close to 50 pounds or more of

bullets applying downward pressure on the reamer.

One of us kept the boxes square and balanced while the

other one turned the tap handle.

Each time we removed the reamer to clean metal chips we

switched places. We

stopped when the rear of the reamer squared off the muzzle

face.

The second

time I did this I made sure the barrel was vertical by placing

a level on top of the steel plate before adding any bullets.

I also put a second steel plate on top of the brown box

shown in the photo above.

With the leveled barrel and extra steel plate I was

able to turn the tap wrench by myself without any additional

assistance. It

took about 90 minutes to ream each barrel using this weighted

method.

Threading

the Barrel

We removed

the brass bushing from the reamer and installed it onto the

tap. We again

applied cutting oil to the bushing and the tap threads and

started cutting the threads.

A little downward pressure got the tap started.

After every half turn we backed off the tap to cut the

chips. We didn’t

have to apply any weight to the tap handle because once the

threads were started the tap pretty much fed itself into the

barrel. After the

tap bottomed out we removed it and thoroughly cleaned out all

remaining oil and metal chips from inside the barrel, then

coated the inside with gun oil.

I had a few

spare flush-mount choke tubes lying around the shop so we

installed an improved cylinder choke into the barrel.

I used some choke tube lube to lubricate the threads

before installing the choke tube.

If I didn’t use the choke tube lube the choke tube

would be very difficult to remove after the barrel and tube

heated up from repeated firings.

Installing

a New Bead

Typically a shotgun bead is mounted 1/2“ to 1” behind the

end of the barrel, but that area would be either

too thin because I reamed it to accept choke tubes, or

would be in the threaded part of the barrel.

I marked the barrel 1 3/4“ back from the end of the

barrel which is behind the choke tube in a thick part of the

barrel.

Finding the

top center line of a round barrel is not always easy.

It’s easy to find the center of the barrel, but if

the barrel is canted the center may not be in line with your

line of sight. There

are a couple of ways to find the center line but I devised a

tool to help with this.

I took a

scrap piece of 1” x 4” wood and milled a V-groove down the

center. Then I

drilled a hole in the center of the groove with a #12 drill

bit. I placed this

on the top end of the barrel with the hole positioned over the

spot where I wanted to mount the bead and held it in place

with a rubber band.

I placed a

3/4“ x 12” aluminum bar on top of the wood and placed a 1

1/2“ x 12” aluminum bar over the sight notch in the

receiver. I

rotated the wood block until the two bars were parallel.

The two aluminum bars were actually my homemade M1

Garand barrel indexing tool (refer to my article Rebarreling

Two M1 Garands). I

inserted the largest hole center punch I purchased from

Brownells #080-732-000

into the hole in the wood block and marked the barrel.

Just to make sure it was correct I taped a piece of

string from the center of the sight notch to the center of the

muzzle and the string fell perfectly across the mark.

I drilled

the bead hole using a #33 drill bit and tapped the hole with

the 6-48 tap. I

made sure there were no burrs left inside the barrel.

The barrel is now ready to receive a bead.

I decided

to make my own bead. Modern

beads are a round ball with a threaded stem, but older beads

were more flat. I

took a 1/8” brass rod and threaded it with a 6-48 die I

purchased from MidwayUSA #136898.

I cut the rod 1/8” above the end of the threads and

dressed the top so that it was flat and the sharp edges were

slightly beveled. I

installed my homemade bead into the bead hole and found that

the threads protruded into the barrel so I used a cutoff wheel

on my high speed rotary tool to trim the threaded end.

I used a little blue Locktite® on the threads to hold

it in place.

Extending

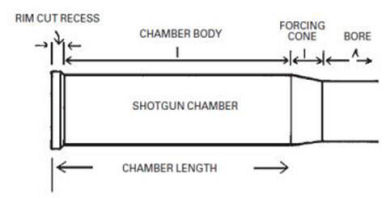

the Forcing Cone

The

forcing cone in a shotgun barrel is the transition from the

wider chamber to the narrower bore. Typically the chamber

is long enough to allow the plastic hull to open completely

so the wad and shot can exit the hull with a minimum of

resistance. The Winchester 97 was originally designed to

shoot 2 3/4” roll-crimp shells. If the forcing cone was too

short for 2 3/4” star-crimp shells the hull would not open

completely which would form a constriction and could cause

an unsafe increase in pressure for a 100-year old gun. This

can also cause a decrease in accuracy due to shot

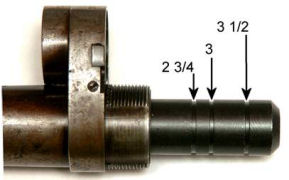

deformation. I purchased a 12-gauge chamber gauge

#080-546-012 and a long forcing cone reamer

#080-661-012 both from Brownells.

I

measured the chamber and found it to be very short. The end

of the chamber should be even with the first groove in the

gauge to accommodate 2 3/4“ shells. As you can see from the

above photo, the chamber was very short. Because this gun

was manufactured in 1907 the chamber was probably cut for 2

3/4” roll-crimp paper shells. Roll-crimp paper shells don’t

open as far as plastic star-crimp shells, so if the previous

owner was shooting 2 3/4“ shells in this barrel, the star

crimp would not be able to open completely causing a

constriction and the pressure would have been increased.

I used

the long forcing cone reamer to lengthen the forcing cone

until the gauge was 0.100” away from the first groove as

shown in the above photo. In a Winchester 97 shot shells

headspace on the headspace ring inside the receiver which is

0.100” thick, so I left the 2 3/4“ groove 0.100” back from

the face of the barrel. Now 2 3/4“ shells will be able to

open completely with no constriction.

(Note:

When I originally performed the work I lengthened the

chamber so the gauge fit up to the 2 3/4“ groove. A reader

of the Kitchen Table Gunsmith pointed out to me that this

would be incorrect and the chamber would be too long so I

have corrected this article. 5/8/2015)

To finish

the job I polished the chamber and new forcing cone with a

12-gauge chamber Flex-Hone® I purchased from Brownells #080-608-512.

This tool is a wire brush with abrasive balls on the

ends of the bristles and comes with a 9-inch shaft.

It requires the use of Brownells Flex-Hone® Oil #080-008-609

to ensure the polishing is performed correctly.

I attached the hone to my drill and applied the oil to

the hone. I

polished the chamber, forcing cone, and barrel by running the

drill at a slow speed (<750 RPM) and moving it in and out.

Since the tool could only polish half of the barrel, I

installed a cylinder choke and polished the front half of the

barrel by inserting the hone from the muzzle.

I flushed the barrel with brake parts cleaner, then

oiled it with CLP. Now

the bore is clean and polished smooth.

Cutting

the Butt Stock

The length of pull (LOP) of this gun just felt too long to me.

Plus, if I was to use it for Cowboy Action Shooting™

I wanted to try to load with my right hand and I really had to

stretch to reach the ejection port.

There are a number of methods for measuring LOP, but it

boils down to how it ultimately feels to the shooter.

With the gun mounted on my shoulder I measured from the

tip of my nose to the first knuckle of my thumb, which

measured exactly 2-inches.

For correct LOP this measurement should be between 1”

and 1 1/2“. To

facilitate loading with my right hand I wanted the stock to be

a little bit shorter so I decided to remove 1”, and since

the new recoil pad I was adding was 3/4“ I would have to

remove 1 3/4“ inches from the butt stock.

The other

measurement I needed to take into account was pitch.

Pitch can best be described as the angle of the butt in

relation to the receiver and barrel.

I set the butt flat on a window sill so the end of the

receiver was just touching the edge of the window frame.

As you can see in the above photo the barrel was angled

away from the window frame.

So this gun has up or positive pitch.

(Think of it this way, you have to climb up

hill from muzzle to receiver.)

You will almost never see neutral or down (negative)

pitch. Negative

pitch would have the heel of the stock (top) sticking out

farther from the toe (bottom) which would make it difficult to

mount and could cause bruising of the shoulder.

To find the

degrees of pitch I measured the distance from the window frame

to the tip of the barrel which was 1.127”.

The distance from the point where the receiver touched

the window frame to the end of the muzzle was 22” which

formed the hypotenuse of a right triangle.

So using the formula ARCSIN(1.127/22) gave me an angle

of 2.9 degrees of positive pitch.

I removed

the stock from the receiver and put a strip of masking tape

around the stock where I planned to cut.

I adjusted the fence on my table saw to cut 1 3/4”

and laid the butt against the fence.

I adjusted the miter gauge so it was in line with the

top of the stock at the 2.9-degree setting and cut the stock.

Installing

a Recoil Pad

I purchased a grind-to-fit Kick

Eez® recoil pad from MidwayUSA #926512

to add to the butt stock to help dampen some of the recoil.

The original butt stock measured 1 5/8” wide by 4

7/8” long; the new recoil pad measured 2” wide by 5 5/8”

long and 3/4“ thick so there was plenty of pad to grind off

and fit.

When I cut

the stock I also cut off both holes so I had to drill two new

holes. This is

much better than having to fill and re-drill an existing hole.

I marked the center of the butt stock and marked where

I wanted to drill the first hole.

There are two pencil lines in the above photo, my first

line was not in the center.

I used a #28 drill bit to drill the first hole, then

drove the screw into the hole to cut the threads.

I mounted the recoil pad onto the butt stock with the

first screw and inserted the second screw.

I rotated the pad so the second screw would leave a

mark; where that mark intersected the pencil line I drilled

the second hole.

I mounted

the oversized recoil pad onto the butt stock and scribed a

line around the outer edge of the butt stock.

I removed the recoil pad and used an 80-grit sanding

belt on my belt sander to grind the pad down to the scribe

line. I did this

in three stages:

Stage

1: I ground the

sides and the top of the recoil pad flat up to the scribe

line.

Stage

2: I mounted the

recoil pan onto the butt stock and ground the toe at the same

angle as the stock again, up to the scribe line.

Stage

3: I remove the

recoil pad and finished grinding the bottom sides to the

scribe line

I took some

220-grit sand paper and rounded the sharp edges on the soft

surface of the recoil pad that were left from the grinding.

I also sanded the newly ground sides to smooth down the

surfaces. I

finished by coating all surfaces with paste wax.

I installed

the butt stock onto the receiver, then installed the recoil

pad onto the butt stock. I

was really quite pleased with the results.

The length of pull is now much better for me and the

gun fits my shoulder perfectly.

I can reach the ejection port much more easily with my

right hand for loading single shells for cowboy matches.

With the

shortened barrel, shortened butt stock, and new magazine tube

spring and follower I loaded five 2 3/4“ dummy shells into

the magazine and tested all of the functions.

The shotgun functioned perfectly and all shells fed and

ejected as they should. So

now my 100-year old great deal is ready for 21st

century competition.

I already

had most of the tools mentioned in this article.

I purchased the chamber gauge and a forend retaining

nut wrench #080-548-012

from Brownells. New

parts and tools cost me a little over $60.00 which still made

this gun a great deal.

Addendum

10/17/2014

Photo Courtesy The Online

Outpost

As

mentioned before this gun was originally designed to hold

six 2 5/8” shells, but would only hold five 2 3/4“ shells.

I purchased a 6-round conversion kit from

The Online Outpost which consists of a new, aluminum

follower and a shorter magazine tube spring. It works

because when the shorter spring collapses it allows more

room in the tube for a full six rounds.

Wild

Bunch Match October 25, 2014

Finally, after almost a year of preparation, I attended my

first Wild Bunch match sponsored by the

Walnut Grove Rangers in Ellenboro, NC. We fired 25

shotgun rounds spread over six stages. My modified

Winchester 97 functioned flawlessly! I did not have any

jams, failure to feed or failure to eject malfunctions.

Other shooters had problems with their 97’s but mine worked

perfectly. While working on this gun I discovered that I

could not “short-stroke” it; it needed to be pumped fully to

the rear, and fully to the front. If I didn’t use complete,

full strokes the gun would jam up and I would have to finish

the full stroke. So I practiced working the gun at home

using dummy rounds.

Since I

had never fired the gun prior to the match, the match

officials allowed me to try it out before the match

started. I loaded six shells in the magazine and pumped and

fired them as quickly as I could. Since I had no problems I

felt the gun was ready for competition.

Believe

it or not, I had two stages where I missed a shotgun

target! Well, as they say, there is no target big enough,

or close enough that you can’t miss. Now if I can only get

the hang of loading one shell at a time for cowboy

shooting.

|